Historical links between Brittany and USA

BREIZH AMERIKA strives to highlight the long history of friendship and cooperation between Brittany, France and the United States of America. From the large number of Breton sailors and soldiers that left the ports of Brittany to participate in the American Revolution, the 800,000 American GI's that disembarked in Brest to fight in WWI, and the large emigration from Central Brittany to North America over the last century has helped create an undeniable link.

Liens historiques entre la Bretagne et les USA

BREIZH AMERIKA souligne la longue histoire d'amitié et de coopération entre la Bretagne, la France et les États-Unis d'Amérique. Du grand nombre de marins et de soldats bretons qui ont quitté les ports de Bretagne pour participer à la Révolution américaine, les 800 000 GI américains qui ont débarqué à Brest pour combattre dans la Première Guerre mondiale, et la grande émigration de la Bretagne centrale vers l'Amérique du Nord (Bretons de New York, Bretons de Californie, Bretons d'Amérique) au cours du siècle dernier a aidé à créer un lien indéniable.

Ces Bretons d'Amérique

An exposition is organized annually in July and August by Bretagne Transamerica at the Chateau de Tronjoly in the city of Gourin, France, tracing the history and stories of emigration of over 100,000 Bretons to North America.

http://btagourin.com

Une exposition est organisée chaque année en juillet et août par Bretagne Transamerica au Château de Tronjoly dans la ville de Gourin, en France, retraçant l'histoire et les histoires d'émigration de plus de 100 000 Bretons vers l'Amérique du Nord.

http://btagourin.com

Une exposition est organisée chaque année en juillet et août par Bretagne Transamerica au Château de Tronjoly dans la ville de Gourin, en France, retraçant l'histoire et les histoires d'émigration de plus de 100 000 Bretons vers l'Amérique du Nord.

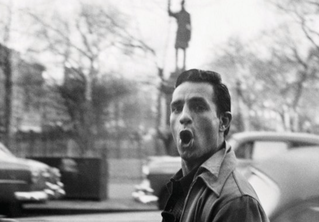

Was Jack Kerouac really Breton?

At the height of his literary success, Jack Kerouac set off to France with no intention of doing a book tour or taking a vacation. At the age of 43, the American author yearned for his roots after decades of wandering. Kerouac, who recounted his expedition in Satori in Paris (1966), was determined to locate signs of his ancestor after landing in Paris on June 1, 1965 and traveling to Brittany.

Despite his 'Satori' title (“Japanese for ‘sudden illumination'”), Kerouac only found dead ends when reading French archives and searching for namesakes. He recounts staying at Hotel Bellevue in Brest and talking about horse races with the owner of the bar La Cigale. Georges Didier, nicknamed “Fournier” in his novel. Didier was interviewed by Hervé Quéméner years later:

“A guy came in who seemed to me to have already had a few drinks. He ordered a brandy and we started talking.”

It is Georges Didier who gives him the contact of Pierre Le Bris (called "Ulysse" in Satori in Paris) who was a publisher and bookseller in Brest.

Kerouac soon met with Pierre

“It was in my apartment, above the bookstore, that I welcomed Kerouac, whose books I knew. He sat down at my bedside and began to talk to me about his ancestors; I showed him my family tree (...). Some time later, I thought we had a common origin when I discovered a stone's throw from the family farm in Plomelin [southern Finistère], a pond bearing the name of Kervoac'h.”

The two men would continue to write to each other but would never meet again.

Plans for more trips to Brittany were derailed by Kerouac's failing health, and he died four years after that first visit.

Learn more about Kerouac's breton roots

Despite his 'Satori' title (“Japanese for ‘sudden illumination'”), Kerouac only found dead ends when reading French archives and searching for namesakes. He recounts staying at Hotel Bellevue in Brest and talking about horse races with the owner of the bar La Cigale. Georges Didier, nicknamed “Fournier” in his novel. Didier was interviewed by Hervé Quéméner years later:

“A guy came in who seemed to me to have already had a few drinks. He ordered a brandy and we started talking.”

It is Georges Didier who gives him the contact of Pierre Le Bris (called "Ulysse" in Satori in Paris) who was a publisher and bookseller in Brest.

Kerouac soon met with Pierre

“It was in my apartment, above the bookstore, that I welcomed Kerouac, whose books I knew. He sat down at my bedside and began to talk to me about his ancestors; I showed him my family tree (...). Some time later, I thought we had a common origin when I discovered a stone's throw from the family farm in Plomelin [southern Finistère], a pond bearing the name of Kervoac'h.”

The two men would continue to write to each other but would never meet again.

Plans for more trips to Brittany were derailed by Kerouac's failing health, and he died four years after that first visit.

Learn more about Kerouac's breton roots

Joseph-Yves Limantour, San Francisco's richest man?

In the mid-19th century, a Breton captain, Joseph-Yves Limantour, was the owner of more than half of San Francisco and the islands of the Bay. He went on to make his fortune in Mexico, where his son became a minister, after his claim to be one of the world's richest men was overturned by an American court.

We know very few details about the youth of Joseph-Yves Limantour, born in 1812, in Ploemeur, Brittany, France. He was the eldest of a family of six children and his father was a guard in the port of Lorient. At 19, like many inhabitants of the Lorient region he joined the merchant navy.

For 5 years, he sailed in the Atlantic transporting goods and people between Vera Cruz and France. In 1836, after crossing Cape Horn, he continued his shipping activities based in Lima, Peru. As a trader and ship captain, he explored new economic opportunities along the Pacific coasts, from Valparaiso (Chile) to California. On October 26, 1841, his schooner, the Ayacucho, ran aground at the entrance to San Francisco Bay. A dense fog had caused him to miss the famous Golden Gate, at the entrance of the Bay. With his men, he traveled to Sausalito where he chartered a boat to collect his shipwrecked merchandise: silks, spirits, equipment and food that had been destined for settlers. The salvage was a considerable success and he was eventually able to make significant profits from his sales leading him to stay in the Yerba Buena pueblo for a year. At the time California was part of Mexico and in 1842, Limantour loaned money to the Mexican governor, Manuel Micheltorena, who offered land in the area in lieu of payment.

Learn more about Joseph-Yves Limantour

In the mid-19th century, a Breton captain, Joseph-Yves Limantour, was the owner of more than half of San Francisco and the islands of the Bay. He went on to make his fortune in Mexico, where his son became a minister, after his claim to be one of the world's richest men was overturned by an American court.

We know very few details about the youth of Joseph-Yves Limantour, born in 1812, in Ploemeur, Brittany, France. He was the eldest of a family of six children and his father was a guard in the port of Lorient. At 19, like many inhabitants of the Lorient region he joined the merchant navy.

For 5 years, he sailed in the Atlantic transporting goods and people between Vera Cruz and France. In 1836, after crossing Cape Horn, he continued his shipping activities based in Lima, Peru. As a trader and ship captain, he explored new economic opportunities along the Pacific coasts, from Valparaiso (Chile) to California. On October 26, 1841, his schooner, the Ayacucho, ran aground at the entrance to San Francisco Bay. A dense fog had caused him to miss the famous Golden Gate, at the entrance of the Bay. With his men, he traveled to Sausalito where he chartered a boat to collect his shipwrecked merchandise: silks, spirits, equipment and food that had been destined for settlers. The salvage was a considerable success and he was eventually able to make significant profits from his sales leading him to stay in the Yerba Buena pueblo for a year. At the time California was part of Mexico and in 1842, Limantour loaned money to the Mexican governor, Manuel Micheltorena, who offered land in the area in lieu of payment.

Learn more about Joseph-Yves Limantour

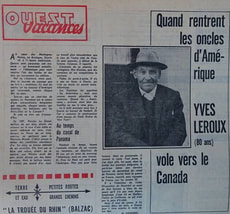

Sur les traces du « Consul Breton » de New York

Entre 1927 et 1930, Yves LeRoux fut peut-être le plus connu des Bretons de New York. Dans son bar clandestin, « Le Consul breton », ses compatriotes immigrants n’étanchaient pas seulement leur soif… L’heure de gloire d’Yves Le Roux sonne en 1928 et 1929, dans le New York de la prohibition où son bar clandestin (son speakeasy),

Le Consul Breton, est le rendez-vous des Bretons de New York, à la recherche d’un coup à boire, d’un coup de main, d’un emploi, d’un logement, de nouvelles du pays ou … d’une jolie femme. Yves Le Roux est au centre de ce réseau, mais côtoie aussi la pègre new yorkaise qui l’approvisionne en boissons alcoolisées illégales.

Il affirmera même avoir eu de bonnes relation avec ... Al Capone lui-même.

La Grande Aventure des Bretons d'Amérique

Il y a 140 ans, un certain Nicolas Le Grand et deux de ses amis quittent les Montagnes Noires en sabots, direction l’Amérique ! Leur retour triomphal quelques années plus tard amorcera une vague d’émigration massive et pourtant méconnue, qui concernera plus de 100 000 Bretons téméraires, fuyant outre- Atlantique la misère de campagnes surpeuplées.

Hiver 1881, Roudouallec, Morbihan. Nicolas Le Grand est fatigué. Fatigué de trimer pour un salaire de douze sous par jour. Une mi- sère. Tailleur de pierre de métier, cet homme de 29 ans peine à remplir les assiettes de ses deux petites filles et de sa femme, Marie-Françoise. Dans cette Bretagne rurale et surpeuplée de la fin du 19e siècle, il n’y a pas d’avenir pour des garçons comme lui.

Savoir plus sur Nicolas Le Grand et la grands aventure des Bretons des USA

Hiver 1881, Roudouallec, Morbihan. Nicolas Le Grand est fatigué. Fatigué de trimer pour un salaire de douze sous par jour. Une mi- sère. Tailleur de pierre de métier, cet homme de 29 ans peine à remplir les assiettes de ses deux petites filles et de sa femme, Marie-Françoise. Dans cette Bretagne rurale et surpeuplée de la fin du 19e siècle, il n’y a pas d’avenir pour des garçons comme lui.

Savoir plus sur Nicolas Le Grand et la grands aventure des Bretons des USA

The Stars and Stripes first saluted in Brittany

Spend any time in the United States and you will immediately learn that Americans have a very patriotic attachment to the American flag and national anthem. Do you the history of when the Stars and Stripes was officially recognized by a foreign power? And did you know that it happened in Brittany, France?

On this day on February 14, 1778, French Admiral de La Motte-Picquet's fleet was anchored in the bay of Quiberon in Brittany. The French Royal Navy was guarding its strategic port of Lorient and fishing and trading ships in the area faced with growing English threats.

Also in the area was the USS Ranger, an American sloop of war armed with 18 guns, commanded by John Paul Jones. Jones had been aggressively hunting English ships along the coasts of Brittany and then receiving resupplying assistance in Breton ports.. That day, the USS Ranger sailed from Quiberon with a flag with red and white stripes on her stern, adorned with 13 stars on a blue background. This was the new star-spangled banner, the Stars and Stripes, which the young American nation had adopted on June 14, 1777.

At the site of the French fleet the USS Ranger fired a salute of thirteen cannon shots, as many as the number of US states. Admiral La Motte-Picquet, aboard the Robuste, a 74-gun vessel, responded with nine shots, the regulatory figure at the time for an independent republic. In doing so, he officially recognizes the United States of America. It is the first time that the American flag has been entitled to the military honors from another country.

The symbolic event was larger relayed across Europe and greatly angered the British crown. This salute at sea from a French ship, however, had the effect of recognizing the independence of the United States by France.

On this day on February 14, 1778, French Admiral de La Motte-Picquet's fleet was anchored in the bay of Quiberon in Brittany. The French Royal Navy was guarding its strategic port of Lorient and fishing and trading ships in the area faced with growing English threats.

Also in the area was the USS Ranger, an American sloop of war armed with 18 guns, commanded by John Paul Jones. Jones had been aggressively hunting English ships along the coasts of Brittany and then receiving resupplying assistance in Breton ports.. That day, the USS Ranger sailed from Quiberon with a flag with red and white stripes on her stern, adorned with 13 stars on a blue background. This was the new star-spangled banner, the Stars and Stripes, which the young American nation had adopted on June 14, 1777.

At the site of the French fleet the USS Ranger fired a salute of thirteen cannon shots, as many as the number of US states. Admiral La Motte-Picquet, aboard the Robuste, a 74-gun vessel, responded with nine shots, the regulatory figure at the time for an independent republic. In doing so, he officially recognizes the United States of America. It is the first time that the American flag has been entitled to the military honors from another country.

The symbolic event was larger relayed across Europe and greatly angered the British crown. This salute at sea from a French ship, however, had the effect of recognizing the independence of the United States by France.

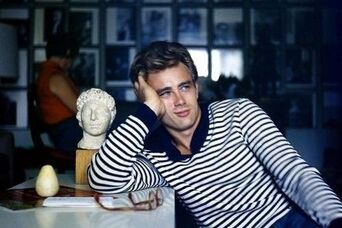

The History of the Breton Shirt

The tale of the Breton begins in 1858, when the French navy adopted a white cotton pullover with horizontal indigo blue stripes as its official uniform. Because of the contrast of the indigo stripes against the white main body of the uniform, as seamen fell overboard, it was easier to spot them. The shirt also had three-quarter length sleeves and a boat neckline — a low cut hem around the neck — so it could be quickly removed and waved around, making the missing sailor easy to find.

The Breton originally had twenty-one stripes, a reference to Napoleon's twenty-one naval victories over the English. It was made by independent tailors in Brittany, a cottage industry of sorts. “The body shall have 21 white stripes, each twice as wide as the 20 or 21 navy blue stripes,” according to the Act. A striped cotton shirt is now known as a Breton shirt, regardless of the thickness and number of stripes, as well as the color of the stripes.

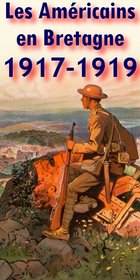

Les Américains en Bretagne (1917-1919)

Véritable porte d'entrée de l'Europe, la Bretagne a créé, au fil des décennies, des liens étroits avec les Etats-Unis. C'est ainsi dans le petit port de Saint-Goustan, à Auray, que l'un des pères fondateurs des Etats-Unis, Benjamin Franklin, débarque en 1776 pour demander de l'aide aux Français contre les Britanniques. Bien plus tard, c'est encore à Brest et à Saint-Nazaire que la majorité des troupes américaines arrivent pour épauler les armées françaises et britanniques lors de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Entre 1917 et 1919, plus de 200 000 sammies transitent alors par la région de Nantes, ils sont près de 800 000 à débarquer à Brest pour la seule année 1918. Mais la Bretagne n'est pas qu'un lieu de passage, au contraire. Les gigantesques camps de Pontanézen (Finistère) et de Montoir-de-Bretagne (Loire-Inférieure) accueillent jusqu'à 60 000 soldats chacun. Les autres départements bretons ne sont pas en reste puisqu'ils reçoivent également d'importants contingents d'hommes à Saint-Brieuc (Côtes-du-Nord), à Cesson-Sévigné (Ille-et-Vilaine), à Coëtquidan ou encore Meucon (Morbihan). Ce dernier exemple est significatif. En 1918, près de 4 000 ouvriers s'activent à construire ex-nihilo des infrastructures (baraquements, écuries, gare, aérodrome, hôpital, entrepôts…) pouvant recevoir près de 10 000 soldats, tout en se servant d’une partie des installations existantes dans le camp militaire français, notamment le champ de tir. A ces camps s'ajoutent également les différentes bases de surveillance maritime comme à Paimbœuf (dirigeables), à l’Île Tudy (hydravions) ou encore à Quiberon (escadrille côtière

Entre 1917 et 1919, plus de 200 000 sammies transitent alors par la région de Nantes, ils sont près de 800 000 à débarquer à Brest pour la seule année 1918. Mais la Bretagne n'est pas qu'un lieu de passage, au contraire. Les gigantesques camps de Pontanézen (Finistère) et de Montoir-de-Bretagne (Loire-Inférieure) accueillent jusqu'à 60 000 soldats chacun. Les autres départements bretons ne sont pas en reste puisqu'ils reçoivent également d'importants contingents d'hommes à Saint-Brieuc (Côtes-du-Nord), à Cesson-Sévigné (Ille-et-Vilaine), à Coëtquidan ou encore Meucon (Morbihan). Ce dernier exemple est significatif. En 1918, près de 4 000 ouvriers s'activent à construire ex-nihilo des infrastructures (baraquements, écuries, gare, aérodrome, hôpital, entrepôts…) pouvant recevoir près de 10 000 soldats, tout en se servant d’une partie des installations existantes dans le camp militaire français, notamment le champ de tir. A ces camps s'ajoutent également les différentes bases de surveillance maritime comme à Paimbœuf (dirigeables), à l’Île Tudy (hydravions) ou encore à Quiberon (escadrille côtière

The Monuments Men in Brittany

John Davis Skilton

Prior to his service in the U.S. Army, Skilton worked as a curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Along with other future Monuments Men, Craig Hugh Smyth, Charles Parkhurst, and Lamont Moore, he took part in the evacuation of seventy-five of the museum’s most important works to the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina. From January to June of 1943, Skilton supervised the maintenance and care of the artworks as a curator in residence at their temporary home. Soon after, he was called on to join the MFAA as the Allied troops prepared for their invasion of Normandy.

After D-Day in 1944, Skilton joined troops on their march across northern France, inspecting and repairing great cultural monuments along the way. On August 28, 1944, American troops entered the small town of Plougastel-Daoulas, near the city of Brest. Lt. Skilton was among them, and noticed a damaged Calvary scene near a destroyed church. The large monument was like many others built across Brittany, a four-sided sculpture representing scenes from life and death of Christ. This particular Cavalry was most likely constructed in 1598 by the Sire de Kereraod to praise God for having brought an end to the plague in Plougastel. Skilton, in awe of its beauty and understanding of its cultural value, collected the numerous statues from the damaged Calvary and stored them in the attic of the presbytery. He pledged to help salvage the grand sculpture if he survived the war, and upon his return home to the States, founded the Plougastel Calvaire Restoration Fund to raise funds for the restoration. The work was completed in 1948-49 by the sculptor John Millet. For his dedication to the town, Skilton was named an Honorary Citizen of Plougastel on July 16, 1959 and a town square was also named after him.

Benjamin Franklin arrives in St Goustan

On October 26, 1776, exactly one month to the day after being named an agent of a diplomatic commission by the Continental Congress, Benjamin Franklin sets sail from Philadelphia for France, with which he was to negotiate and secure a formal alliance and treaty. Franklin arrived on December 4th in the Breton port of St Goustan, Auray.

In France, the accomplished Franklin was feted throughout scientific and literary circles and he quickly became a fixture in high society. While his personal achievements were celebrated, Franklin's diplomatic success in France was slow in coming. Although it had been secretly aiding the Patriot cause since the outbreak of the American Revolution, France felt it could not openly declare a formal allegiance with the United States until they were assured of an American victory over the British.

For the next year, Franklin made friends with influential officials throughout France, while continuing to push for a formal alliance. France continued to secretly support the Patriot cause with shipments of war supplies, but it was not until the American victory over the British at the Battle of Saratoga in October 1777 that France felt an American victory in the war was possible.

A few short months after the Battle of Saratoga, representatives of the United States and France, including Benjamin Franklin, officially declared an alliance by signing the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance on February 6, 1778. The French aid that these agreements guaranteed was crucial to the eventual American victory over the British in the War for Independence.

Sur La Piste Des Emigrants Bretons En Amerique

Les liens historiques entre la Bretagne et les États-Unis sont toujours forts, notamment grâce à une forte émigration depuis le centre de la Bretagne.

Pour mieux comprendre ce que ces immigrants ont vécu en arrivant en Amérique, nous partageons cet extrait du bulletin « PENN-AR-BED » de 1953.

A la fin du XIXe siècle, ils ont débuté comme ouvriers agricoles ou comme jardiniers dans les riches propriétés des environs de Lenox dans le Massachusetts, puis, à l'exemple des Bretons de chez nous, ils sont allés se fondre dans le prolétariat des grandes villes américaines, particulièrement à New-York et dans sa banlieue.

Curieuse destinée que celle de ces paysans des Montagnes Noires, jetés hors de leur aire natale par la nécessité et la force de leur vitalité, et qui luttent de .toute leur énergie dans les ·hôtels ou les usines de la première ville du monde.

On peut dire que 3 Bretons sur 4 travaillent dans les hôtels de New-York, les uns comme garçons de salle, aides-cuisiniers, cuisiniers ou sous-chefs dans les plus beaux établissements, les autres comme serveurs ou garçons dans les restaurants de deuxième ordre ou dans les cafés. ... LIRE PLUS

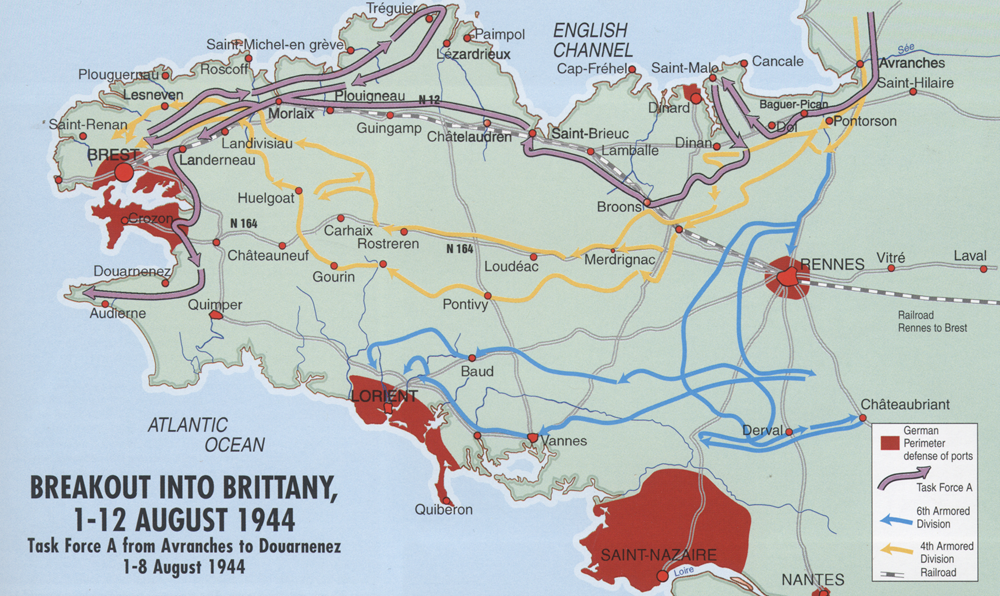

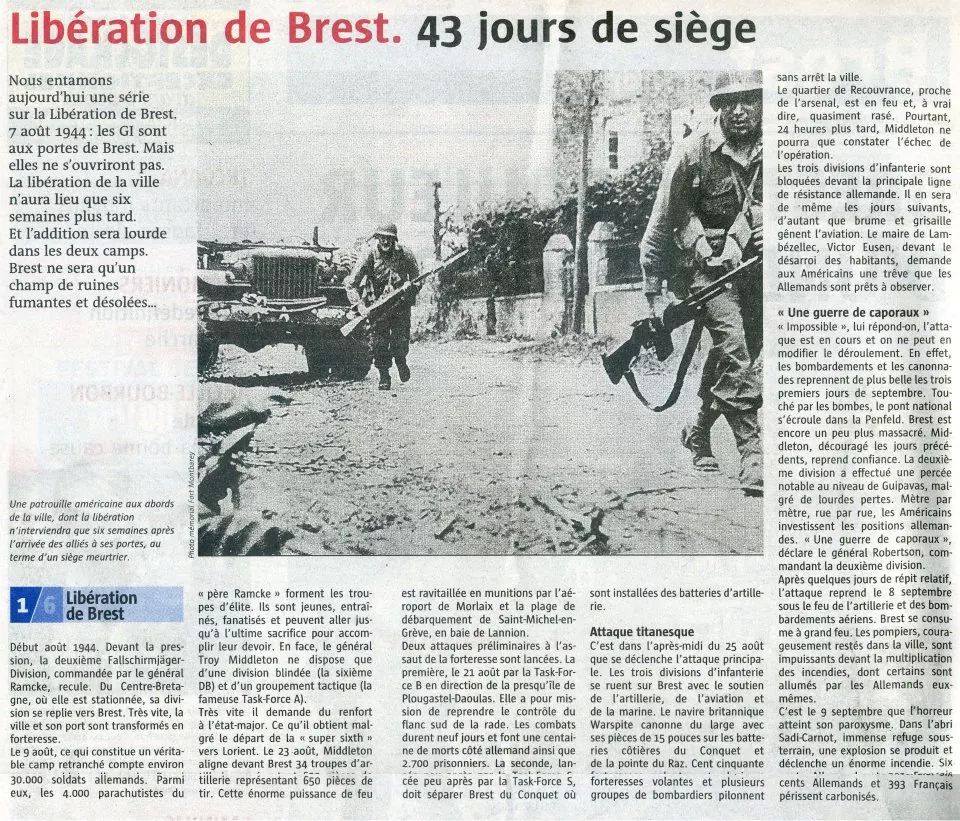

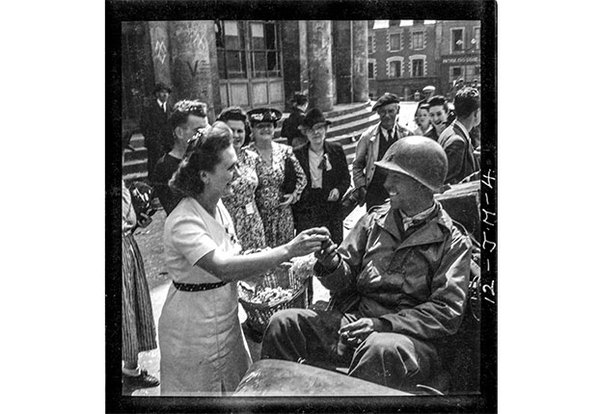

World War II, Breakout into Brittany

The Battle for Brittany took place between August and October 1944. After breaking out of the Normandy beach head in June 1944, Brittany was targeted because of its naval bases at Lorient, St. Nazaire and Brest. By the time of Germany's surrender in Brest on September 18th, the Americans had lost 10,000 killed and wounded. Brest was destroyed - including its harbour. Rather than risk the same at Lorient and St. Nazaire, the Americans simply surrounded the ports for the rest of the war.

Liberation de Brest

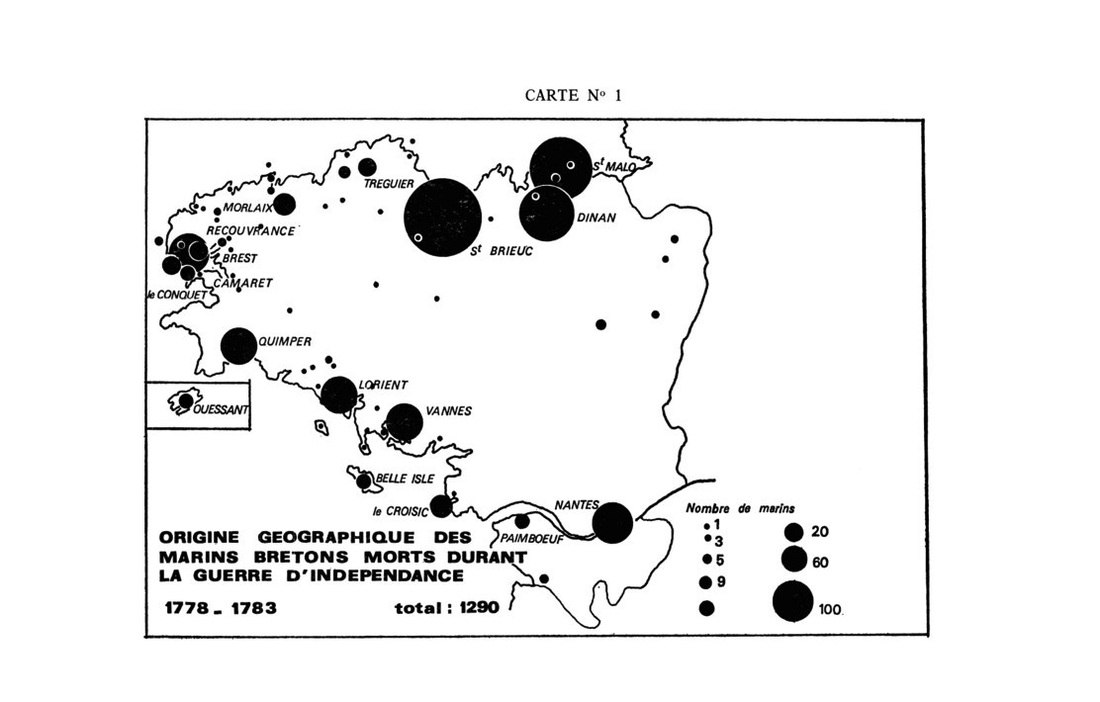

Bretons sailors serving in the American Revolution

The port of Brest, which was the largest military harbor in France or even Europe at the time, played a key role in the deployment of French forces that participated in operations in the Americas on the side of the colonists. The fleets of Admirals d'Estaing, Lamotte-Piquet, Suffren, Count de Grasse, and troops of Rochambeau all left from Brest. A majority of sailors of the French fleet were of Breton origin. Records reveal high levels of recruitment across Brittany for service in the Americas.

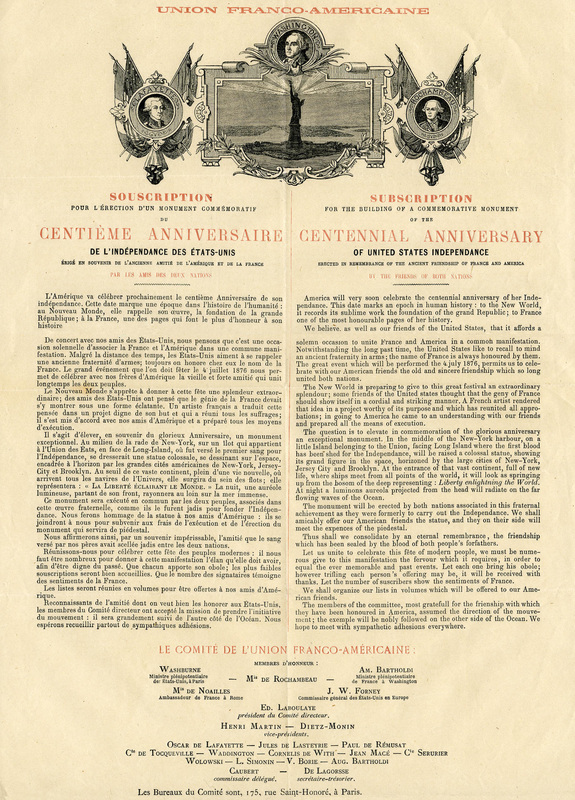

Quand Quimper finançait la statue de la Liberté de New-York

C’est un fait certainement peu connu mais la Ville de Quimper a participé au financement de la statue de la Liberté érigée à la suite du centenaire de la fête de l’Indépendance américaine célébrée en 1876.

Le 30 mai 1876 le Conseil municipal de Quimper votait une subvention de 100 francs or. Le 1er juillet 1876 le président Laboulaye écrivait au maire de Quimper : Le comité de l’Union Franco-Américaine a l’honneur de vous adresser tous ses remerciements pour la part que la Ville de Quimper prend à notre œuvre de fraternisation. Nous sommes heureux de pouvoir vous inscrire sur notre livre d’or qui doit être offert en album aux Etats-Unis pour être conservé dans leurs archives, l’adhésion de la ville de Quimper.

Le projet finalement retenu en 1879 allait représenter la Liberté éclairant le monde. Il s’incarnerait dans un personnage féminin d’inspiration classique, drapé, avec un bras levé, portant une torche, alors que l'autre retenait une tablette gravée, un diadème lui scindant la tête. Quimper y avait apporté sa pierre.

NY Times focus on Breton immigration

They had been on their feet all day, waiting on table or working in kitchens. They were on their feet all night, dancing, at the 17th annual Brittany Ball, held last Saturday at Manhattan Center. And a lot of them were dancing again on Sunday, above La Grillade restaurant.

Almost all French restaurants were represented at the ball, because almost all French restaurants have waiters or bus boys or cooks who hail from Brittany. And many of them come from one small town and its farming environs, the town of Gourin.

When they first came here in the early part to this century, the Bretons worked, played and stayed so tightly together in New York that few of them learned to speak English. Nevertheless, they were promptly dubbed The Americans when they returned home. Today, most of them seem to pick up English quite fast, perhaps because not all of them still live together in the Forties around Ninth Avenue. Many have moved to Astoria, Queens, and a few live on the East Side.

The Bretons, who are a Celtic people (they were driven out of England by the Anglo-Saxons about 14 centuries ago), have no great culinary tradition. “But they have a natural feel for cooking,” said Mrs. Robert Low, wife of the councilman, who has had a succession of Breton housekeepers. Mrs. Low, who said that a Breton never left without ... {READ MORE}

Almost all French restaurants were represented at the ball, because almost all French restaurants have waiters or bus boys or cooks who hail from Brittany. And many of them come from one small town and its farming environs, the town of Gourin.

When they first came here in the early part to this century, the Bretons worked, played and stayed so tightly together in New York that few of them learned to speak English. Nevertheless, they were promptly dubbed The Americans when they returned home. Today, most of them seem to pick up English quite fast, perhaps because not all of them still live together in the Forties around Ninth Avenue. Many have moved to Astoria, Queens, and a few live on the East Side.

The Bretons, who are a Celtic people (they were driven out of England by the Anglo-Saxons about 14 centuries ago), have no great culinary tradition. “But they have a natural feel for cooking,” said Mrs. Robert Low, wife of the councilman, who has had a succession of Breton housekeepers. Mrs. Low, who said that a Breton never left without ... {READ MORE}

The World War I Naval Monument at Brest

The World War I Naval Monument at Brest, France stands on the ramparts of the city overlooking the harbor which was a major base of operations for American naval vessels during the war. The original monument built on this site to commemorate the achievements of the U.S. Navy during World War I, was destroyed by the Germans on July 4, 1941, prior to the United States entry into World War II. The present structure is a replica of the original and was completed in 1958.

Brest is the westernmost port of France. Its location and activities there have been vital in commerce and conflicts over the centuries. Brest was especially important to many missions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during 1917 and 1918.

The monument is a rectangular rose colored granite shaft rising 145 feet above the lower terrace and 100 feet above the Cours d'Ajot. It sits upon a German bunker complex at the approximate site of the original monument. All four sides of the monument are decorated with sculpture of naval interest. The surrounding area has been developed by ABMC into an attractive park.

The Naval Monument at Brest displays this inscription in both English and French:

Erected by the United States of America to commemorate the achievements of the naval forces of the United States and France during the world war.

It was the principal port of embarkation and debarkation of troops, equipment, and supplies. Of the more than 2,000,000 members of the AEF arriving in France, more than 700,000 flowed through Brest. Brest served as American Naval Headquarters in France. Its ships and aircraft performed escort duties for convoys to and from France, as well as fighting the German submarine menace.

A force of more than 30 destroyers and dozens of smaller subchasers performed the many missions to ensure safety of the sea. The Naval Air Service, flying airplanes and dirigibles, supplemented the surface forces. During July and August, 1918, more than 3,000,000 tons of shipping was convoyed in and out of French ports by vessels based at Brest. The AEF’s Services of Supply (SOS) Base Section No. 5 set up depots to accommodate arriving and departing troops. For example, its billeting facilities at Brest could accommodate 55,000 persons. The SOS operated a variety of installations in the Brest locale for assembly and delivery of vehicles and equipment to forward units.

The Naval Monument at Brest rises above a park along the Cours Dajot, overlooking the harbor. It is 800 meters southwest of the Gare de Brest.

Brest is the westernmost port of France. Its location and activities there have been vital in commerce and conflicts over the centuries. Brest was especially important to many missions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) during 1917 and 1918.

The monument is a rectangular rose colored granite shaft rising 145 feet above the lower terrace and 100 feet above the Cours d'Ajot. It sits upon a German bunker complex at the approximate site of the original monument. All four sides of the monument are decorated with sculpture of naval interest. The surrounding area has been developed by ABMC into an attractive park.

The Naval Monument at Brest displays this inscription in both English and French:

Erected by the United States of America to commemorate the achievements of the naval forces of the United States and France during the world war.

It was the principal port of embarkation and debarkation of troops, equipment, and supplies. Of the more than 2,000,000 members of the AEF arriving in France, more than 700,000 flowed through Brest. Brest served as American Naval Headquarters in France. Its ships and aircraft performed escort duties for convoys to and from France, as well as fighting the German submarine menace.

A force of more than 30 destroyers and dozens of smaller subchasers performed the many missions to ensure safety of the sea. The Naval Air Service, flying airplanes and dirigibles, supplemented the surface forces. During July and August, 1918, more than 3,000,000 tons of shipping was convoyed in and out of French ports by vessels based at Brest. The AEF’s Services of Supply (SOS) Base Section No. 5 set up depots to accommodate arriving and departing troops. For example, its billeting facilities at Brest could accommodate 55,000 persons. The SOS operated a variety of installations in the Brest locale for assembly and delivery of vehicles and equipment to forward units.

The Naval Monument at Brest rises above a park along the Cours Dajot, overlooking the harbor. It is 800 meters southwest of the Gare de Brest.

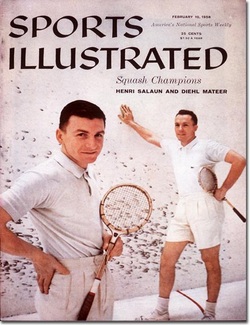

Henri Salaun: "widely considered one of the world’s most influential squash players."

We are sharing with you today the amazing story of Breton-born Henri Salaun. Possibly the only Breton to ever be featured on the cover of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED.

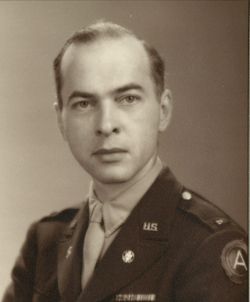

Born in Brest, he was forced to flee the city as German troops invaded on May 10, 1940. Immigrating to Boston he excelled at racket sports at Wesleyan University. After serving in the US Army in WWII, he returned to the United States and began one of the finest professional squash careers in history.

He won the first international U.S. Open of squash in 1954 (then called the North American Open) — the final was a high-profile match against Pakistan’s Hashim Khan. Salaun also went on to win America’s national championship four times (1955, 1957, 1958, 1961), and was an eight-time winner of the Canadian Open. It’s a long and intriguing success story — one that begins with a harried departure from pre-war France, winds through the Wesleyan University campus in Middletown, climbs to the highest of highs in professional squash, then quietly settles down to a home in Needham, Mass.

This is the story of Henri Salaun.

He’s widely considered one of the world’s most influential squash players, and cut his teeth as a three-sport athlete at Wesleyan in the 1940s. Salaun, 87, went on to win the inaugural U.S. Open of squash in 1954, earned a bevy of national championships and even adorned the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1958. But like so many people of his era, Salaun’s life wasn’t shaped by sports. It was shaped by World War II. His Wesleyan career was bifurcated by World War II — that’s a story we’ll get to in a bit — but his first run-in with the war was as a 14-year-old boy in Brest, France. Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940, then started funneling troops toward the coastal northwest where Salaun lived with his mother. Amid growing tension and fear, Salaun’s mother caught word of a boat leaving for England. Immediately, she packed up her things and instructed her son to do the same. In a matter of moments, the two were driving to the coast (about 20 miles away). Once at the docks, they ran the last half-mile or so as German scouts watched from a nearby hill.

“We ran and ran,” Salaun recalled in a Monday phone interview. “My mother went to the man in charge of the boat — ‘Monsieur, you must take me and my son. We can’t stay here.’”

It was minutes before the boat was to set sail, but the man acquiesced. After a month in England, Salaun’s mother made contact with Arthur Hill, a friend living in Boston. At that time, immigrants needed an American sponsor to travel to the United States. Hill, a lawyer, gladly helped out. Salaun and his mother hopped the next boat, crossed the Atlantic and landed in Boston. His mother, fluent in English and French, quickly got a job at the French consulate and found an apartment on Beacon Street. Salaun, meanwhile, knew little English and had yet to begin American schooling. So he would go to Boston’s museums and movie theaters, trying to soak up what English he could.

Once comfortable with the language, he began attending Deerfield Academy, where he began expressing himself with a more universal language: sports. Salaun was a natural athlete: he had grown up playing tennis in France. He picked up squash and soccer at Deerfield Academy, and quickly became one of the school’s finest talents. He was given a free membership to Boston’s esteemed University Club on Beacon Street (not far from the apartment where he and his mother first lived) and in a matter of years became the club’s top player.

In the meanwhile, Salaun was accepted to Wesleyan — thanks in part to a connection between the Deerfield Academy headmaster and Wesleyan president Victor L. Butterfield, who was also a Deerfield alum.

At Wesleyan, Salaun earned All-American honors in soccer and competed nationally in tennis and squash. He studied languages, and joined the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity on campus.

But two years into his college career, he was drafted.

Fluent in French and English, Salaun was of great value to the army. He was immediately sent to Germany — returning to Europe not five years after leaving his home in the Brittany region of France — and spent time not far from the French border.

At one point, Salaun survived a German ambush. The rest of his unit did not, and the 19 year old was utterly alone in the German countryside.

“I was surrounded by Germans, and I somehow ended up in the middle of this big field,” Salaun remembered. “All of my mates were dead. And there was a little cabin — filled with tools and farming equipment. I got in unnoticed and hid there.”

Salaun hid all night, lying still under blankets and benches. The German troops never entered the cabin, and Salaun managed to make it back to the American lines the next morning. Not long after, Salaun received an honorable discharge, and like many young soldiers, returned to America and their college careers.

“It was an interesting time on campus,” Salaun said. “Things had changed. Everyone was a little more accustomed to life — I think that’s the best way to describe it. And we started college again.”

Salaun returned to his squash career, graduated in 1949, and then began one of the finest professional squash careers in history.

He won the first international U.S. Open of squash in 1954 (then called the North American Open) — the final was a high-profile match against Pakistan’s Hashim Khan. Salaun also went on to win America’s national championship four times (1955, 1957, 1958, 1961), and was an eight-time winner of the Canadian Open.

He was perhaps the “most astute strategist and counter-puncher in the game,” squash writer Rob Dinerman wrote in 2002. “His retrieving, patience, willingness to play long points and deft execution of lobs and front-wall shots (all of which seemed to die just before reaching the far side wall) provided potent antidotes to power players.”

Dinerman likened Salaun’s playing style to the “murderous aplomb of a dinner guest quietly pocketing his host’s most expensive silverware.” Salaun continued to play competitively into his 70s, and his loss in the U.S. 70-and-over final in 2002 came 51 years after his first national tournament appearance. Salaun is a member of the inaugural class of the U.S. Squash Hall of Fame in 2000, and also part of the first Wesleyan Athletics Hall of Fame class in 2008.

“Since the induction and creation of the Hall of Fame, it’s given Wesleyan an opportunity to fully appreciate his legacy,” current Wesleyan squash coach Shona Kerr said. “He quietly went forth and created an amazing squash career — now we have the privilege to acknowledge and appreciate that.”

Salaun later began Henri Salaun Sports Inc., a sporting equipment company in New Hampshire. He now lives in Needham with his wife of 63 years, Emily.

The Middletown Press

Born in Brest, he was forced to flee the city as German troops invaded on May 10, 1940. Immigrating to Boston he excelled at racket sports at Wesleyan University. After serving in the US Army in WWII, he returned to the United States and began one of the finest professional squash careers in history.

He won the first international U.S. Open of squash in 1954 (then called the North American Open) — the final was a high-profile match against Pakistan’s Hashim Khan. Salaun also went on to win America’s national championship four times (1955, 1957, 1958, 1961), and was an eight-time winner of the Canadian Open. It’s a long and intriguing success story — one that begins with a harried departure from pre-war France, winds through the Wesleyan University campus in Middletown, climbs to the highest of highs in professional squash, then quietly settles down to a home in Needham, Mass.

This is the story of Henri Salaun.

He’s widely considered one of the world’s most influential squash players, and cut his teeth as a three-sport athlete at Wesleyan in the 1940s. Salaun, 87, went on to win the inaugural U.S. Open of squash in 1954, earned a bevy of national championships and even adorned the cover of Sports Illustrated in 1958. But like so many people of his era, Salaun’s life wasn’t shaped by sports. It was shaped by World War II. His Wesleyan career was bifurcated by World War II — that’s a story we’ll get to in a bit — but his first run-in with the war was as a 14-year-old boy in Brest, France. Germany invaded France on May 10, 1940, then started funneling troops toward the coastal northwest where Salaun lived with his mother. Amid growing tension and fear, Salaun’s mother caught word of a boat leaving for England. Immediately, she packed up her things and instructed her son to do the same. In a matter of moments, the two were driving to the coast (about 20 miles away). Once at the docks, they ran the last half-mile or so as German scouts watched from a nearby hill.

“We ran and ran,” Salaun recalled in a Monday phone interview. “My mother went to the man in charge of the boat — ‘Monsieur, you must take me and my son. We can’t stay here.’”

It was minutes before the boat was to set sail, but the man acquiesced. After a month in England, Salaun’s mother made contact with Arthur Hill, a friend living in Boston. At that time, immigrants needed an American sponsor to travel to the United States. Hill, a lawyer, gladly helped out. Salaun and his mother hopped the next boat, crossed the Atlantic and landed in Boston. His mother, fluent in English and French, quickly got a job at the French consulate and found an apartment on Beacon Street. Salaun, meanwhile, knew little English and had yet to begin American schooling. So he would go to Boston’s museums and movie theaters, trying to soak up what English he could.

Once comfortable with the language, he began attending Deerfield Academy, where he began expressing himself with a more universal language: sports. Salaun was a natural athlete: he had grown up playing tennis in France. He picked up squash and soccer at Deerfield Academy, and quickly became one of the school’s finest talents. He was given a free membership to Boston’s esteemed University Club on Beacon Street (not far from the apartment where he and his mother first lived) and in a matter of years became the club’s top player.

In the meanwhile, Salaun was accepted to Wesleyan — thanks in part to a connection between the Deerfield Academy headmaster and Wesleyan president Victor L. Butterfield, who was also a Deerfield alum.

At Wesleyan, Salaun earned All-American honors in soccer and competed nationally in tennis and squash. He studied languages, and joined the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity on campus.

But two years into his college career, he was drafted.

Fluent in French and English, Salaun was of great value to the army. He was immediately sent to Germany — returning to Europe not five years after leaving his home in the Brittany region of France — and spent time not far from the French border.

At one point, Salaun survived a German ambush. The rest of his unit did not, and the 19 year old was utterly alone in the German countryside.

“I was surrounded by Germans, and I somehow ended up in the middle of this big field,” Salaun remembered. “All of my mates were dead. And there was a little cabin — filled with tools and farming equipment. I got in unnoticed and hid there.”

Salaun hid all night, lying still under blankets and benches. The German troops never entered the cabin, and Salaun managed to make it back to the American lines the next morning. Not long after, Salaun received an honorable discharge, and like many young soldiers, returned to America and their college careers.

“It was an interesting time on campus,” Salaun said. “Things had changed. Everyone was a little more accustomed to life — I think that’s the best way to describe it. And we started college again.”

Salaun returned to his squash career, graduated in 1949, and then began one of the finest professional squash careers in history.

He won the first international U.S. Open of squash in 1954 (then called the North American Open) — the final was a high-profile match against Pakistan’s Hashim Khan. Salaun also went on to win America’s national championship four times (1955, 1957, 1958, 1961), and was an eight-time winner of the Canadian Open.

He was perhaps the “most astute strategist and counter-puncher in the game,” squash writer Rob Dinerman wrote in 2002. “His retrieving, patience, willingness to play long points and deft execution of lobs and front-wall shots (all of which seemed to die just before reaching the far side wall) provided potent antidotes to power players.”

Dinerman likened Salaun’s playing style to the “murderous aplomb of a dinner guest quietly pocketing his host’s most expensive silverware.” Salaun continued to play competitively into his 70s, and his loss in the U.S. 70-and-over final in 2002 came 51 years after his first national tournament appearance. Salaun is a member of the inaugural class of the U.S. Squash Hall of Fame in 2000, and also part of the first Wesleyan Athletics Hall of Fame class in 2008.

“Since the induction and creation of the Hall of Fame, it’s given Wesleyan an opportunity to fully appreciate his legacy,” current Wesleyan squash coach Shona Kerr said. “He quietly went forth and created an amazing squash career — now we have the privilege to acknowledge and appreciate that.”

Salaun later began Henri Salaun Sports Inc., a sporting equipment company in New Hampshire. He now lives in Needham with his wife of 63 years, Emily.

The Middletown Press

Château de Kerjean almost sold to Henry Clay Frick in early 1900's

In the early 1900's, a number of wealthy Americans were seeking to purchase the 16th century Château de Kerjean which is located in Saint-Vougay, Brittany. It was even rumored that famous industrialist H. C. Frick was one of the perspective buyers, proposing to ship the castle piece by piece back to America. In 1909, two American architects travelled to Brittany to make accurate plans of the chateau. The castle was finally sold to the French Government in 1911 for $50,000 by the Countess de Coatgourden.

Le long calvaire de la Bretagne

John G. Morris/Contact Press Images

John G. Morris/Contact Press Images

Eisenhower a souligné le rôle militaire de la Résistance bretonne lors de la Libération, mais elle a eu un rôle civil tout aussi important, avec l'installation des autorités provisoires prévues par le Gouvernement provisoire de la République française (GPRF).Ce satisfecit ne doit pas faire oublier le prix payé, conséquence d'une répression accrue. Entre la fin de l'année 1943 et le 6 juin 1944, les arrestations de résistants bretons se multiplient. Comme celle, le 10 décembre 1943, de Maurice Guillaudot, commandant de gendarmerie du Morbihan, mais aussi chef départemental de l'Armée secrète (AS) qui a transmis des rapports sur « le panier de cerises », nom de code pour l'état de la défense allemande et son implantation. Malgré ces interpellations, l'activité et les effectifs de la Résistance augmentent sans cesse. Mais la route est encore longue entre le débarquement en Normandie et la libération totale de la Bretagne, après le 8 mai 1945.

PARACHUTAGE À L'AVEUGLE

Appliquant, dès le signal donné sur la BBC, les plans de sabotage des Alliés destinés à paralyser l'ennemi, des groupes de résistants passent à l'action dans la nuit du 5 au 6 juin, puis les jours suivants, retardant l'acheminement de troupes et de matériel allemands vers le front normand ; certaines colonnes mettront ainsi deux semaines pour aller de Redon à Avranches (150 km). La nouvelle du débarquement entraîne un afflux de jeunes vers les maquis. Mais les résistants manquent d'armes, même si des parachutages, après le 6 juin, améliorent la situation.

L'opération alliée déterminante en Bretagne est menée par des parachutistes français du 4e bataillon de SAS (Special Air Service, une unité des forces spéciales britanniques) dirigé par le commandant Bourgoin, dit « le Manchot » – blessé lors de combats en Tunisie, il a été amputé du bras droit en février 1943. Quatre sticks (groupes de combat) de près d'une quarantaine d'hommes doivent créer deux bases pour accueillir les autres éléments du bataillon. Leur objectif est d'évaluer les forces allemandes et les possibilités d'action avec la Résistance. ... Lire Plus

PARACHUTAGE À L'AVEUGLE

Appliquant, dès le signal donné sur la BBC, les plans de sabotage des Alliés destinés à paralyser l'ennemi, des groupes de résistants passent à l'action dans la nuit du 5 au 6 juin, puis les jours suivants, retardant l'acheminement de troupes et de matériel allemands vers le front normand ; certaines colonnes mettront ainsi deux semaines pour aller de Redon à Avranches (150 km). La nouvelle du débarquement entraîne un afflux de jeunes vers les maquis. Mais les résistants manquent d'armes, même si des parachutages, après le 6 juin, améliorent la situation.

L'opération alliée déterminante en Bretagne est menée par des parachutistes français du 4e bataillon de SAS (Special Air Service, une unité des forces spéciales britanniques) dirigé par le commandant Bourgoin, dit « le Manchot » – blessé lors de combats en Tunisie, il a été amputé du bras droit en février 1943. Quatre sticks (groupes de combat) de près d'une quarantaine d'hommes doivent créer deux bases pour accueillir les autres éléments du bataillon. Leur objectif est d'évaluer les forces allemandes et les possibilités d'action avec la Résistance. ... Lire Plus

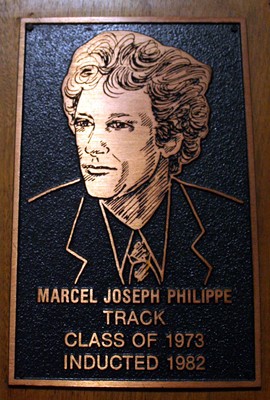

Marcel Philippe, Breton-American competes in 1976 Olympics for France

In 1973, when MARCEL PHILIPPE, a native New Yorker, was named to the French track and field team, he could hardly speak French. Now he speaks it so well that he spent the last two weeks in New Orleans as the expert commentator for French television at the United States Olympic track and field trials.

Philippe was a half-miler and miler at Fordham University, good enough to have won the 800-meter silver medal in the 1973 World University Games. His parents, Yves and Leonne, were born in Brittany, France (Yves became a celebrated chef in New York, known as Philippe of the Waldorf).

"They could speak English," the son said. "In fact, my mother was a graduate of Hunter College. But French was more natural to them. They spoke to my sister and me in French and we talked to them in English. I understood French, but I didn't speak it much then."

Philippe, 40 years old, lives in Manhattan and is a lawyer in the Manhattan District Attorney's office. At the track trials, he was on television live from 30 minutes to three hours a day.

"I'm comfortable with the French language," he said, "but I'm not 100 percent with it. I have a very good vocabulary, but I'm always amazed at how many nuances there are in the language, how it is so much more precise than English. When you juggle the vocabulary, you can be more precise. I'm getting there."

NY Times 29/06/1992

Philippe was a half-miler and miler at Fordham University, good enough to have won the 800-meter silver medal in the 1973 World University Games. His parents, Yves and Leonne, were born in Brittany, France (Yves became a celebrated chef in New York, known as Philippe of the Waldorf).

"They could speak English," the son said. "In fact, my mother was a graduate of Hunter College. But French was more natural to them. They spoke to my sister and me in French and we talked to them in English. I understood French, but I didn't speak it much then."

Philippe, 40 years old, lives in Manhattan and is a lawyer in the Manhattan District Attorney's office. At the track trials, he was on television live from 30 minutes to three hours a day.

"I'm comfortable with the French language," he said, "but I'm not 100 percent with it. I have a very good vocabulary, but I'm always amazed at how many nuances there are in the language, how it is so much more precise than English. When you juggle the vocabulary, you can be more precise. I'm getting there."

NY Times 29/06/1992

Copyright 2014 - All rights reserved - Breizh Amerika - Privacy Policy