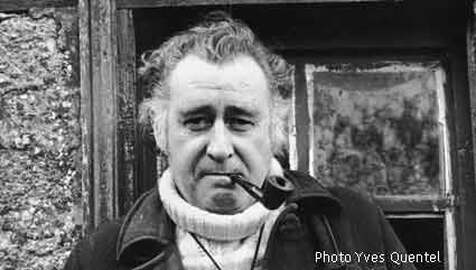

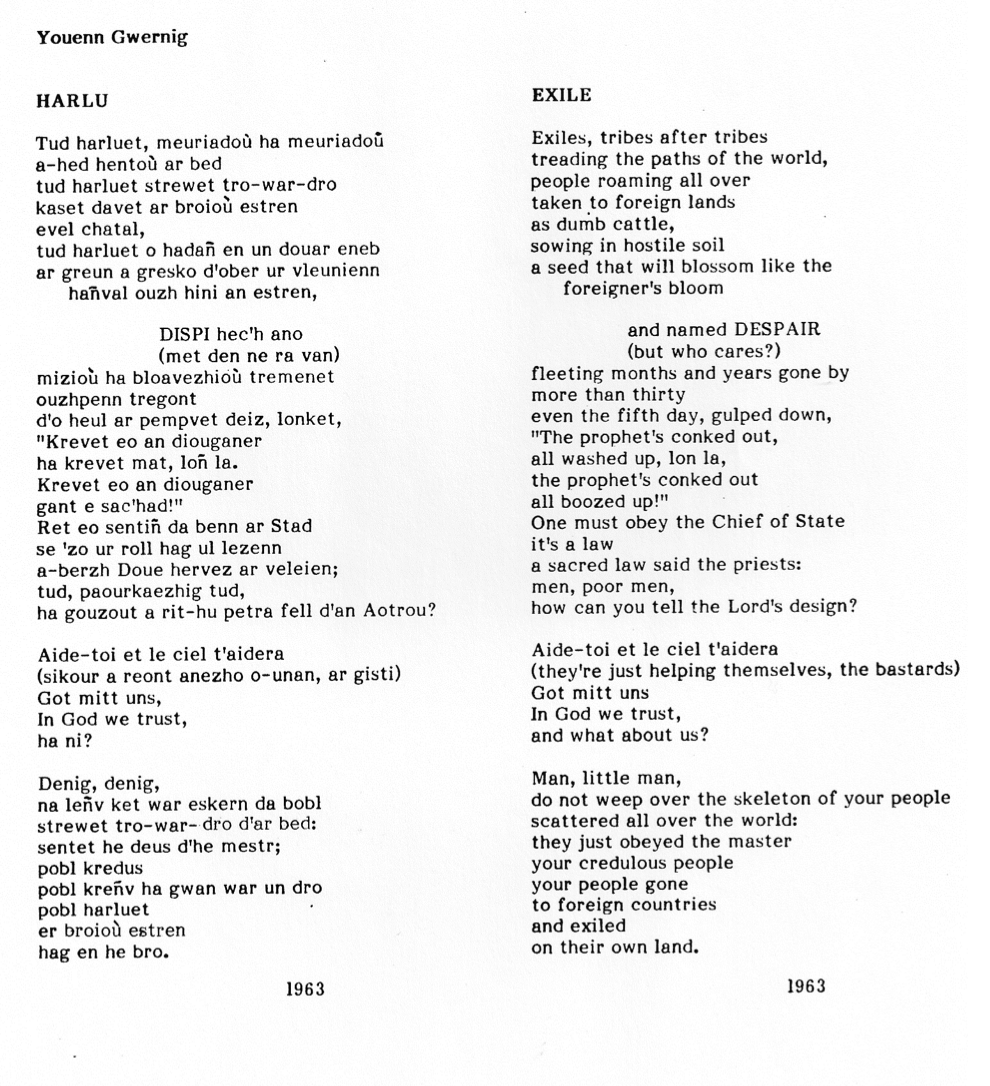

AN INTRODUCTION TO YOUENN GWERNIG Written by Lois Kuter - August 1983, ICDBL newsletter Youenn Gwernig came to the United States in 1957 at the age of 32. His reasons were not different from those of other Bretons who had preceded him or who followed later. With a sister already in New York, emigration seemed the best means to solve the difficult problem of earning a living. But there was also the problem of "feeling at home" at home -- an uneasiness which was perhaps more subconscious than conscious. Although today Brittany seems alive with a youth determined to revive their heritage and create a new one of their own, in the early 1950's Bretons concerned about the future of their nation might well have felt disheartened. Some felt it would be better to feel like a stranger elsewhere. Arriving in New York, Youenn Gwernig worked as a dishwasher and waiter, but most of his 12 years there were spent using his woodworking skills in a factory which reproduced Louis XV style furniture--a job of dull assembly line work and three hours of subway commuting each day. With the supplemental income of his wife Suzig who worked in the cont check of a bowling club, the Gwernigs were able to provide for three daughters- Annaïg, Mari-Loeiza and Gwenola--and indulge in some of the taken for granted comforts of American life. But the money ran out when Suzig's mother (also in the U.S.) needed hospitalization and an operation. Without insurance, the bills piled up. In 1965 mother, daughter and granddaughters returned to Brittany while Youenn stayed behind to pay off the debts. By the time he got back to Brittany in 1969, the debts were paid and he was as poor as when he had left Brittany, but Youenn Gwernig had also become known and respected in Brittany as a Breton language poet. If the United States holds memories of long and hard work hours, it also holds memories as the place where he really started to write--and his writing was in Breton. During the years in New York Youenn Gwernig combed the Breton collection of the New York public library and sent for books from Brittany. The return mail carried his poems and stories to Al Liamm.* Residence on Ryer Avenue in the Bronx introduced Youenn Gwernig to the unmelted pot of urban American cultures. We meet the people of his American experience in his songs, poems and stories, But, one of Gwernig's best known acquaintances in the U.S. was another Breton, Jack Kerouac, whose family (Le Bris de Kerouac) traces back to the Côtes-du-Nord before its arrival in the "New World" in the 18th century. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, Kerouac was proud of both his Breton and Native American roots.** Youenn Gwernig is not known in Brittany today, however, because he befriended a famous writer. He is known ‘in his own right as a singer, poet, and wood sculpter, as well as defender of Breton freedom to be Breton, It was the desire to be Breton in Brittany as well as the desire to rejoin his family that took him back in 1969 to stay. A sense of freedom was immediate. In an article written in 1980 about Gwernig, Yvon Le Vaillant recounts how, at 6 a.m. on his first morning back in the town of Huelgoat in the Arrez Mountains of central west Brittany, Youenn ran down to the lake bordering the town and yelled "No subway today!" Reassured by the echo of the lake he went back to bed.*** Since his return to Brittany, Youenn Gwernig has lived in a small village just outside Huelgoat--a singer, poet and sculpter who loves long walks in the wild countryside and forests of the area. He continues to sing and to write and to insist on the freedom to be Breton in Brittany. The freedom to be a Celt is an important theme in all of Gwemig's writing. It was in the anonymity of American crowds and the greyness of New York City that he came to write down many of his thoughts about his own identity, his feelings for his native country, and the experience of emigration. We have two contributions to this special newsletter which present Youenn Gwernig to you. First, the poem “Harlu" ("Exile") which speaks for itself. This poem has appeared in the Breton language journal Al Liamm as well as in Yann-Ber Piriou's bilingual Breton/French collection of poetry, Défense de cracher par terre et de parler breton.**** Upon request, Youenn Gwernig has supplied us with an English translation for this news- letter. The second presentation of Youenn Gwernig is by means of a review of his novel La Grande tribu by another Breton emigrant, Hervé Thomas. Much of La Grande Tribu was originally published in Breton in Al Liamm as a series of short stories. The review will tell you that Youenn Gwemnig writes for many other emigrants who have crossed the sea to America. Notes * Al Liamm comes out every two months and is available by sub- iption c/o: Yann-Ber d'Haese, Pont Keryau, 29290 Pleyben Brittany (France). See the U.S. ICDBL Newsletter No. 2 for a description of this important Breton language publication. La Kerouac writes of his search for his Breton roots in his book Satori in Paris (NY: Grove Press, 1966). ** - Yvon Le Vaillant "Le Barde des Monts d'Arrée," Le Nouvel Observateur 825 (30 Aug.-5 Sept 1980), pp. 34-35. For an autobiographical sketch of Youenn Gwernig see: "Barde et Breton d'instinct" in Autrement (special issue: Bretagnes les chevaux d'espoir) 19, June 1979, pp. 74-77; "Pennad Kaoz gant Youenn Gwernig" (interview) in Evid ar Brezhoneg 178, June 1980, pp. 1-6; and "Youenn Gwernig--B.À.S. No. 271" in Ar Soner (special 4Oth anniversary issue) 273, 1983, pp. 18-19. **** Yann-Ber Piriou. Défense de ( er par terre et de p: Breton - poèmes de combat, 19 ° (Paris: P. d. 1971). This collection of poe by 20 contemporary Ereton language poets is highly recommended to readers. Youenn Gwernig poem - HARLU (Exile)LA GRANDE TRIBU. Youenn Gwernig (Paris: Grasset, 1980) Review by Hervé Thomas, 1983 Among all the reasons compelling a Breton to emigrate, there is one that stands out. Some of us who have emigrated are conscious of it, and for more of us it's all the way in the back of our minds. At one point we realize that the elements important to the realization of a harmonious and mentally and physically satisfying existence are not there. We have been denied the right to think that those elements are there. Youenn Gwernig describes this in La Grande Tribu through the main character, Ange Rosso, a Breton emigrant to New York whose name come from his Italian father who worked as a stone cutter in the quarries of western Brittany. Ange Rosso cannot forget the reasons that. made him leave his nation. Not unlike Youenn Gwernig himself, he was a native Breton speaker, an accomplished piper, and a person directing his life according to the natural tendencies that make Celts behave, adapting their own cultural, emotional and physical capabilities to their natural surroundings. Ange Rosso has undoubtedly a Celtic atavism. “The worst was the sudden transformation of mentalities... like, all of a sudden everybody was ashamed of what they used to be... I do not believe that I am one to put the bottom on the ball. I had even dreamed of a Breton Nation which would have found again its memory, its culture, îts pride, in order to finally get hold of its history and open itself to the future. But not the future that was starting to develop under my very own eyes, and was com- ing to look more and more like a voluntary genocide. I was starting to look at myself as a remnant of a forgotten era, like a displaced person, and with all evidence as one who was rejected from his sphere. My wife, craving for modernism, left me because of my lack of social ambitions and my Celtic esoterism, predicting for me the dim future of ending up as an absolute derelict outcast. All of a sudden my entire nation seemed to feel like my wife. How soon was my nation going to leave me?" (pp. 182-183). Ange Rosso felt then that he was lost in his own natural environment. Therefore, he took steps to evade the sights of destruction that his sensitivity exposed him to, and came to the United States. When one reads Gwernig's book, one is appalled by the traumatic experiences Ange had to face before he decided to make the move (the departure of his wife, the exodus of Bretons armed him in search of jobs, and the loss of his best friend--almost a son to him--in the Algerian War). My purpose here, however, îs not to describe those experiences in detail, but to help the reader be more aware of some of the thoughts and feelings that are part of the experience of Breton emigration. For those of us who have emigrated, the fact that we did not have to deal with such tragic events does not mean that we were not aware of the inadequacies inherent to the transformed nation in which we were living. Some of us close to our roots tried to react against modernistic bureaucratic oppression by using clumsy methods, violent reactions, and reckless behavior. Some of us tried to find a happy medium between the modern presentations and the concrete elements inherent to our culture, habits and emotions. But, deep down in our soul, we knew that the principal elements which would contribute to our quest for recognition, respect and acceptance by foreign powers and nations (France and nations within France) were smothered by the invasion of artificial ideas born out of modernistic greed and ancient drive for the assertion of power over others. The very young people in Brittany--those able to understand words--have been listening to the older generations, and those generations never fail to bring up stories about generations before, for it. is imbedded in their soul. But, by the time the young people get to school they have already been exposed to a different world which offers them few options--options which are only the sum of added confusions. Although disenchanted by the thinking of some members of the Breton Nation, Youenn Gwernig is clear about the options he feels each Breton must face. "It is the duty of our people to know whether they belong to, and in, Brittany or not. If they are stupid enough to let themselves be drawn into deep French waters or other waters, it is not fair to ask the rest of the world nations to try to correct the result of their own listnessness . . . (Page 264, in answer to a situation where terrorism was presented to Ange Rosso as a means of exposing Brittany to the rest of the world), For those of us who have become conscious of our heritage before or after leaving our nation, it is very easy to think and act as a member of the Breton Nation. We cannot speculate about the outcome of the thinking of the next generation and the generation after that. However, we do feel that Brittany will never cease to exist as a Celtic nation with its own identity. By now readers may have given up hope for a succinct review of La Grande Tribu. Nevertheless, the above comments are necessary to expose readers to the true reasons of Breton denial of their own identity when at home and when travelling to find smaller communities of their own in which they can act as Bretons, speaking Breton, and in which they will gain a sort of experience that will be appreciated the day they are back where they belong. Emigration is not an easy choice for any of us; but as soon as we choose to leave, we end up being with individuals from our own nation seeking the warmth that was lacking in our own surroundings at the time we left. We do find it instantly as soon as we meet other Bretons in places where we can relate to each other. As people belonging in the same place--Brittany--all of a sudden we are aware of our own identity. Those who never spoke Breton try to find every excuse to come up with a few words, even though when they were within the French State boundaries their Breton accent marked them as idiotic "Ploucs" and, out of shame and insecurity, they denied their own identity. Youenn Gwernig's book is a pure rendition of Breton (Celtic) attitudes toward life, its realities, determined thoughts, and a certain way of looking around and living one's life rather than letting it simply go by unnoticed. His presentation of Ange Rosso's experiences (and through them, some of his own) are expressed in a typically Celtic manner, with Breton wit, irony, optimism vs. pessimism, and a fatalistic sense of humor which stresses the importance of living and expressing oneself within the boundaries of actual realities. Youenn Gwernig's sense of humor tends to be very subtle, but very understandable for those who are prepared for it; for others it may be taken as a bitter satire of the world in which we are living. Youenn Gwernig is never confused about issues, values, and forces. His attitude cannot be simplistic. He expresses this thoughts with a true understanding of the difficulties of communicating with concerned but ignorant individuals. It is poetic, realistic, humorous, sad, and a pure definition of a Celtic way of dealing with adversity. The whole story is written with an ironic undertone. Gwernig has rendered in a foreign language (French) the particular style in which a Breton speaker expresses himself. He has described with rare accuracy the life of every Breton in New York, for the form is the same for each one of us--only the details are different. His book is more than a novel. It is a reflection in an excellent literary style of the life, soul and hopes of a real Breton. Bibliography and Discography of works by Youenn GwernigPoetry collections: An Toull en nor (le trou dans la porte). Locmaria-Berrient: Âr MajemEdition, 112 pages, 1972. An diri dir/Stairs of Steel/Escaliers d'acier. Locmaria- Berrien: Ar Majenn Edition, 1976 (trilingual). Novel: La Grande tribu. Paris: Grasset, 1980. (To be translated Into English? - rumors of possibility) Youenn Gwernig regularly contributes to various Breton language publications, most regularly A1 Liamm. Records: Ni hon unan. Arfolk MK2. 45 rpm. Distro ar Gelted (return of the Celts). Arfolk SB309, 1974 E kreiz an noz. Velia 223 0045. 1977 Youenn Gwernig. Production People, 1980.

0 Comments

Louis Kuter, editor of Bro NevezBREIZH AMERIKA PROFILES | Lois Kuter

Lois Kuter has been informing English speaking audiences about Breton culture and language for over 40 years with her subscription based newsletter. Bro Nevez, the longest running Breton newsletter, includes articles about the Breton language and culture, book and music reviews, and short notes to introduce readers to Breton history, art, literature, economy, sports, nature and Brittany's Celtic cousins. Lois is also the only American to have been awarded a Collier de l’Hermine. We sat down with Lois to discuss her connection to Brittany, about the ICDBL, and her thoughts on the future of Breton language. What is your link to Brittany? I have no Breton or Celtic heritage in my family that I know of. My discovery of Brittany was accidental. I’m afraid it is a long story, but I’ll try to keep it short. When I was a teenager I bought an exotic looking musical instrument labeled “Made in Pakistan” which turned out to be the practice chanter for Scottish Highland bagpipes – the basic instrument one uses to learn and practice tunes. I found that there was a bagpipe band in my area – there are many in the U.S. – and I decided to learn. From there I discovered the variety of bagpipes and had the good fortune to meet an uillean piper who took me and a friend on as students. I started on the wooden flute then gradually got up the courage to try the uillean pipes. My piping is very rusty these days and I was never exceptional on either the Highland pipes, uillean pipes or flute, but came to love the music and enjoyed getting together with friends for very informal gatherings where conversation far outweighed music-making. My uillean pipes teacher was interested in all the Celtic languages and cultures and it was at his house that I discovered the music of sonneurs de couple and the bagad, as well as Breton song. I studied anthropology and ethnomusicology as an undergraduate student at Oberlin College and then as a graduate student at Indiana University (Bloomington). When it came time to choose a dissertation topic for my PhD, looking at the relationship of Breton music to Breton identity was a natural choice. And to understand what Breton identity is, it is necessary to look also at language. So I set off for a preliminary look at Brittany the summer of 1975 and then spent an entire year there from September 1978 to September 1979 – certainly a very interesting period in the evolution of Breton identity and music. There have been a few shorter trips since, and I have kept in contact with many friends I made while in Brittany. Music has always been what I love most about Brittany and from 1984 to 1997 I produced 139 hour-long and half-hour-long radio programs for a local radio station here in Philadelphia. While this was a small university station, there were hundreds of listeners who discovered all kinds of Breton music from LPs and CDs of that period in my collection. Tell us about the ICDBL and the newsletter that have been going on for over 40 years? How does someone sign up for it? The International Committee for the Defense of the Breton language was founded in Brussels in 1975. During the years after that over 20 “branches” were established throughout Europe – in most cases a single representative with a particular interest in the Breton language. The idea was to show that it was not just the people of Brittany who were interested in the future of the Breton language. The Brussels base offered the opportunity for the ICDBL to do lobbying on behalf of the Breton language in the European Community. During my stay in Brittany in 1978-79 I was asked to consider setting up a branch of the ICDBL in the U.S. which would add to the presence of a branch already in Canada. The U.S. Branch of the ICDBL was founded in 1981 and we published the first issue of our newsletter that year. Unlike the other branches of the ICDBL, the U.S. branch was a membership organization. Although it has dropped in recent years, annual membership has hovered around 100 individuals from over 40 states and a few provinces of Canada. The focus of activity has always been the newsletter, Bro Nevez, which provides readers with news about the Breton language and efforts to promote it in Brittany as well as information about Breton music, history, economy, cuisine, the natural environment, arts, sports, etc. Besides the newsletter the U.S. ICDBL has written letters of protest to French government officials (usually without response), and we have set up information stands at Celtic Festivals. Because of our dispersal throughout the U.S. we have not held meetings but have a board of consultants who communicate regularly if there are issues to be addressed – elections of new officers, financial matters, changes of membership dues (which remain very low at just $20 a year), or other action that should be addressed as a group. Our members have diverse backgrounds – many with a strong interest in Celtic languages and music, some with a Breton ancestry, others who might have spent vacation time in Brittany, and yet others who simply feel it is important to support minority languages. Most speak neither French nor Breton, so our newsletter has been important in providing access to English language news that has been scarce in either print or more virtual media. All back issues of Bro Nevez are accessible on our website www.icdbl.org to anyone interested, but we welcome new memberships as a way to cover costs of mailing complimentary print copies of the newsletter to individuals and institutions in Brittany who request it in that format. Anyone interested should contact me at [email protected]. What do you see as the future of Breton language? What steps should be undertaken or done? One cannot be overly optimistic about the future of the Breton language, but it seems that Bretons remain diligent in finding as many ways as possible to give it a place in Breton life. The bilingual schools and the immersion style of Diwan continue to grow, but the French Education system seems to throw up roadblocks whenever possible. For example the French Constitution was used to eliminate measures to advance immersion style teaching in the recent Molac law for regional languages. There has been a growth in radio, audiovisual, and other media presence for Breton but there is need for much more growth there. Thanks to the militant efforts of Bretons to insist on bilingual road and street signage, there have been advances there too. I think the amazing creativity and diversity in Breton music has also been a positive factor. Younger Bretons have embraced the traditional heritage of Breton language song and also create new songs in all styles. It will be up to Bretons themselves to ensure the future of the language by learning it and using it in everyday life. And new generations will need to keep up the fight to counteract government roadblocks and resistance to provide real support for regional languages. Easier said than done! |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

June 2024

Breizh Amerikais an organization established to create, facilitate, promote, and sponsor wide-ranging innovative and collaborative cultural and economic projects that strengthen and foster relations and cooperation between the United States of America and the region of Brittany, France. |

Copyright 2014 - All rights reserved - Breizh Amerika - Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed