|

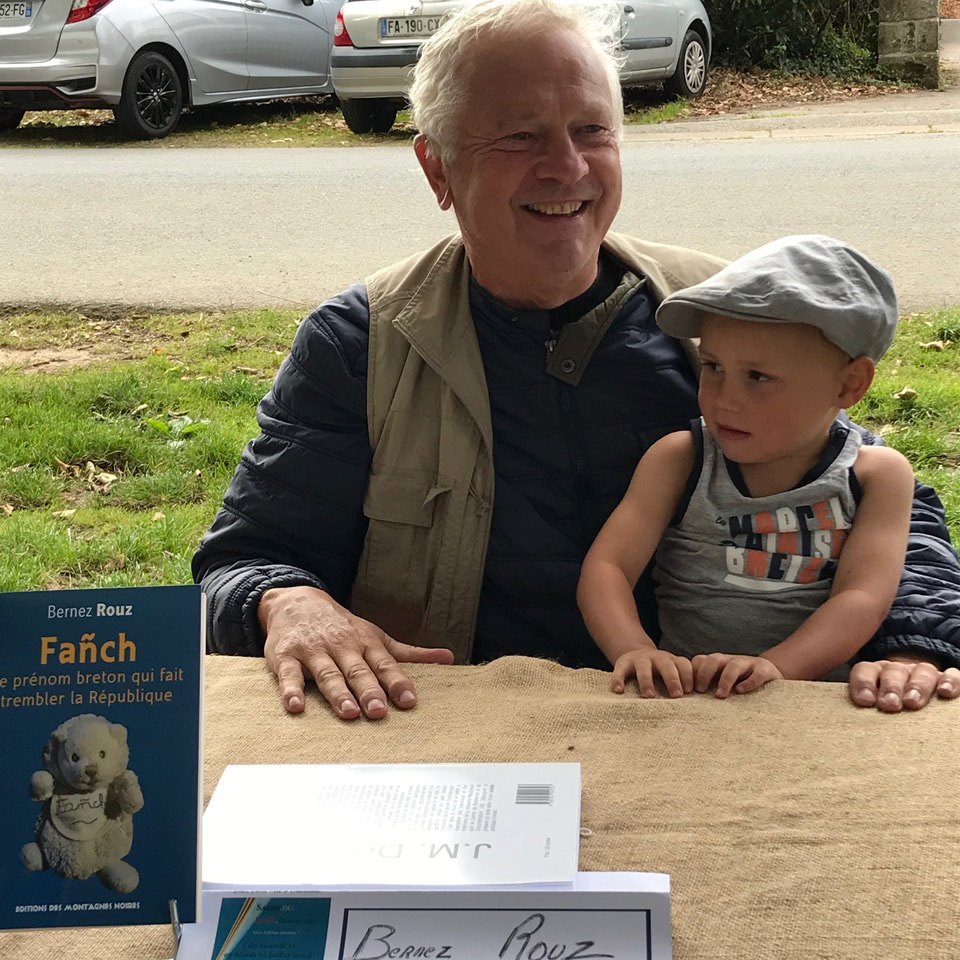

Beaucoup de gens croient que l’affaire Fañch, c’est à dire l’acceptation du tilde sur le n du prénom breton dans l’état civil français est une affaire classée. C’est totalement faux. Depuis Mai 2017, l’affaire Fañch a déclenché une tempête juridique et médiatique démesurée qui a largement dépassé les limites de la Bretagne. Fañch, c’est ce petit garçon né à Quimper à qui on a donné le nom de son grand-père. Mais le fait d’inscrire le tilde sur le n dans l’orthographe bretonne conventionnelle a déclenché les foudres de la justice. Le tilde menace « l’unité du pays » selon la juge de première instance de Quimper. « Le tilde n’est pas inconnu de la langue française » réplique la Cour d’Appel de Rennes. La cour de Cassation prétexte un vice de forme pour ne pas se prononcer. En 2020, l’affaire continue à mobiliser les hommes politiques bretons qui doivent franchir d’innombrables obstacles pour faire admettre l’évidence : le breton est une des langues de France et son orthographe doit être respectée quant au tilde il est bien utilisé dans la langue française depuis plus de mille ans. Bernez Rouz, président du Conseil Culturel de Bretagne a été un des premiers à produire des arguments convaincants sur cette affaire hors norme, en faisant appel à l’histoire des langue s française et bretonne mais aussi aux plus élémentaires droits de l’homme, aux droits linguistiques et culturels. Une affaire Fañch aux USAL’affaire Fañch est suivie de près par les média espagnols, portugais et basques. Car l’acceptation du tilde comme signe diacritique de la langue française signifierait la fin de l’ostracisme envers les prénoms et noms d’origine ibérique. L’affaire concerne aussi les États-Unis car la majorité des états n’acceptent que les signes diacritiques anglais, d’autres par contre acceptent d’autres signes diacritiques dont le tilde. Si 17,6 % des Américains sont d’origine hispaniques, certains états comme le Nouveau Mexique, le Nevada, l’Arizona dépasse les 30 %. Le débat fait rage en Californie ou l’Anglais est langue officielle de l’état depuis 1986. José Medina, un parlementaire hispanique a fait voter une loi pour reconnaitre le ñ dans les documents officiels par 69 voix pour et deux contre. Le gouverneur a jeté son veto sur cette loi, le 10 septembre 2017, c’est à dire au même moment que la décision du juge de Quimper. Cette fois ci ce n’est pas l’unité nationale de la Californie qui est en jeu mais un problème financier car il faudrait parait-il changer le système informatique d’enregistrement. C’est exactement le même argument qu’a avancé notre bien nommé ministre Nuñez devant le sénat. José Medina avait pourtant bien précisé que dans sa loi, tous les signes diacritiques étaient présents sur les claviers d’ordinateur, et ne demandaient donc aucun changement de matériel. Tous les arguments développés par le député californien sont en ligne. [Lire plus] Ils peuvent être repris mot pour mot pour défendre notre identité en respectant les prénoms d’origine, et l’orthographe des langues de France. Le tilde est un combat sans frontière ! 💪  FAÑCH : LE PRÉNOM BRETON QUI FAIT TREMBLER LA RÉPUBLIQUE Depuis mai 2017, l'affaire Fañch a déclenché une tempête juridique et médiatique démesurée qui a largement dépassée les limites de la Bretagne. Fañch, c'est ce petit garçon né à Quimper à qui on a donné le prénom de son grand-père. Mais le fait d'inscrire le tilde sur le "n" dans l'orthographe bretonne conventionnelle a engendré les foudres de la justice.

0 Comments

A young couple from Brittany, France could never have imagined the Breton name they'd chosen for their newborn would create such a judicial firestorm. The use of the name "Fañch" was banned in September 2017 by a tribunal in Quimper stating that the letter "ñ" was incompatible with French law. This initial ruling was brought to a court of appeals by the parents this Monday in Rennes, where the French "avocat général" sadly recommended confirmation of the prior judgment in Quimper. Brittany, the western most peninsula of France, has long had a tradition of un-French sounding names and places names due to the extensive use of the Breton, a celtic language native to the area. French policing of names has lighted since a court ruling in the 1966 allowing Breton names to be officially used administratively. The court ruling in Quimper on September 13, 2017 was surprising to many as Breton names have become very popular throughout Brittany. The bewildering ruling forbid the use of the letter ñ stating, ""would be tantamount to breaking the will of our rule of law to maintain the unity of the country and equality without distinction of origin"*. The letter ñ is common in Breton language but also Spanish, Basque, Galicien, Asturien, Guarani, Tagalog, Hassanya, and Wolof. The court's ruling also stated that ñ was not part of the French language, a reason for it not being used in names. A theory debunked a few days later by Bernez Rouz, President of the Culture Council of Brittany, when he presented numerous official French documents highlighting the use of the letter ñ for centuries, proving it in fact to be part of French orthographic tradition. Following today's appeal the case has been taken under deliberation and a final decision will be rendered on November 19. "We hope for a positive outcome so we can write our son's name as it should," Fañch's mother has stated. "This fight also means defending our heritage, our regional language." A young couple from Brittany, France could never have imagined the breton name they'd chosen for their newborn would create such a judicial firestorm. The use of the name "Fañch" was banned in September by a tribunal in Quimper stating that the letter "ñ" was incompatible with French law. A decision that has prompted the Regional Council of Brittany to petition the Minister of Justice of France to allow the name. Brittany, the western most peninsula of France, has long had a tradition of un-French sounding names and places names due to the extensive use of the Breton, a celtic language native to the area. French policing of names has lighted since a court ruling in the 1966 allowing Breton names to be officially used administratively. The court ruling in Quimper on September 13th was surprising to many as Breton names have become very popular throughout Brittany. The bewildering ruling forbid the use of the letter ñ stating, ""would be tantamount to breaking the will of our rule of law to maintain the unity of the country and equality without distinction of origin"*. The letter ñ is common in Breton language but also Spanish, Basque, Galicien, Asturien, Guarani, Tagalog, Hassanya, and Wolof. The court's ruling also stated that ñ was not part of the French language, a reason for it not being used in names. A theory debunked a few days later by Bernez Rouz, President of the Culture Council of Brittany, when he presented numerous official French documents highlighting the use of the letter ñ for centuries, proving it in fact to be part of French orthographic tradition. The Region Council of Brittany voted this week to solicit the Minister of Justice to ask for the authorization of the diacritical sign and stating that its use in no way threatens the national unity of France. The September 13th court decision is currently being appealed but the affair seems to have many in France questioning why only one official language is recognized in a Republic.where many others are native to the country. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

June 2024

Breizh Amerikais an organization established to create, facilitate, promote, and sponsor wide-ranging innovative and collaborative cultural and economic projects that strengthen and foster relations and cooperation between the United States of America and the region of Brittany, France. |

Copyright 2014 - All rights reserved - Breizh Amerika - Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed