Ker en breton : signification, histoire et omniprésence dans la toponymie et l'anthroponymie6/3/2024 Ker en bretonLe terme "ker" est un élément incontournable de la langue bretonne, dont la présence se retrouve dans d'innombrables noms de lieux et de famille. Véritable marqueur de l'identité bretonne, il témoigne de l'histoire et de la richesse culturelle de cette région. Signification et évolution du terme "ker"À l'origine, "ker" signifiait "place forte" ou "citadelle" en breton, un sens que l'on retrouve dans les termes apparentés "Caer-" en Galles et en Cornouailles. Cependant, dès le Xe siècle, le mot a évolué en Bretagne pour désigner une "ville", une "agglomération urbaine", puis un simple "village", perdant ainsi sa connotation militaire. Omniprésence de "ker" dans la toponymie bretonneLa toponymie bretonne est profondément marquée par la présence de "ker". Dans le seul département du Finistère, on recense plus de 9 000 toponymes comportant cet élément, tandis que les Côtes-d'Armor en comptent plus de 4 200 dans leur partie bretonnante, et le Morbihan près de 4 500. La Loire-Atlantique, bien que moins bretonnante, en compte tout de même 385. À cela s'ajoutent les toponymes en "Car-", variante de "Ker-", dont on dénombre 178 occurrences dans l'ancienne partie bretonnante d'Ille-et-Vilaine et de Loire-Atlantique. Les toponymes en "Ker-" sont généralement composés d'un second élément qui peut être un nom propre (probablement celui de l'ancien chef du village), un terme géographique ou une épithète évoquant l'importance du lieu. Parmi les plus répandus, on trouve Kerangall, Keransquer, Kerautret, Kerbiriou, Kerdanet, Kerdraoñ, Kergrist, Kerloch ou encore Kermarec. "Ker" dans l'anthroponymie bretonneL'influence de "ker" ne se limite pas à la toponymie bretonne, elle se retrouve également dans l'anthroponymie, donnant naissance à de nombreux patronymes. L'un des exemples les plus célèbres est celui de l'écrivain américain Jack Kerouac, dont le nom de famille trouve ses racines dans la langue bretonne. Cette abondance de toponymes en "Ker-" a naturellement engendré pas moins de 470 noms de famille bretons composés de cet élément. Parmi les plus fréquents, on peut citer : Kerangal : Nom breton désignant celui qui habite le lieu-dit Kerangal ou Kerangall, ou qui est originaire d'un hameau portant ce nom. Le toponyme est fréquent en Bretagne, notamment dans le Finistère. Ker signifie village, groupe de maisons, et -angal semble formé sur Gall (nom de baptême ou bien celui qui vient de France), précédé de l'article an. Kerangoarec : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerangouarec, hameau de la commune d'Arzano (29). Variante : Kerangouarec. Le patronyme est porté dans le Morbihan. Signification : le hameau (ker) de Goarec (breton gwareg = lent). Kerbinibin : Originaire de Kerbinibin, hameau de la commune de Plogastel-Saint-Germain (29). Si le premier élément du toponyme est bien connu (ker = hameau), le second est plus mystérieux. Peut-être un ancien nom de personne breton. Plusieurs personnes proposent cependant 'le bon joueur de biniou'. Kerdraon : Nom breton (29) fréquent à Plougastel-Daloulas. Désigne celui qui habite le lieu-dit appelé Kerdraon ou qui en est originaire. Signification du toponyme : ker = groupe d'habitations, hameau + draon (traon) = la vallée, le bas. Kergall : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kergall, toponyme très fréquent en Bretagne (29 hameaux dans les départements 22, 29 et 56). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de (le) Gall, nom de personne et surnom lui aussi très répandu, voir Le Gall. Kergrohen : Celui qui est originaire de Kergrohen, nom de quelques hameaux bretons, notamment dans les communes de Brignogan-Plage (29) et Saint-Igeaux (22). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Grohen, nom de personne à rattacher au gallois crochan (= glouton, vorace). Kerinec, Kérinec : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerinec, nom de plusieurs hameaux, presque tous dans le Finistère (notamment à Plomodiern, Plouzévédé, Poullan-sur-Mer). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Hinec, ancien nom de personne formé sur le breton hin (= ancien, vieux). Keriven, Kerivin : Originaire de Keriven ou Kerivin, nom de nombreux hameaux situés pour la plupart dans le Finistère. Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) d'Iven (voir Evain). Kermadec : Les noms bretons commençant par Ker sont des toponymes, sur lesquels se sont ensuite formés de nombreux patronymes. Le mot ker signifie hameau, village. Ici, le second élément Madec est un nom de personne breton dérivé de l'adjectif mad (= bon). Kermadio (de) : Celui qui a détenu la seigneurie de Kermadio, nom de diverses localités du Morbihan. Puisqu'il s'agit d'une seigneurie, il devrait s'agir du château de Kermadio à Pluneret. Sens du toponyme : le hameau, le village (ker) de Madio, équivalent vannetais de Madiou, diminutif du vieux breton mad (= bon, chanceux, fortuné). Kermeur : Surtout porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kermeur, nom de très nombreux hameaux bretons. Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Meur, le Meur (voir Le Meur). Kerneur : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerneur, nom de hameaux à Pluvigner (56) et Plougastel-Daoulas (29). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Naour, Le Naour, un nom formé sur aour (= or). Kerouanton : Nom assez fréquent en Bretagne (29, 22). Désigne celui qui est originaire de la localité de Kerouanton (commune de Lopérec, 29). Le toponyme est formé avec ker (lieu habité, hameau, village) suivi d'un éventuel *Rouanton (dérivé du vieux breton roiant = royal, selon A. Deshayes). Kerrien : Nom breton. Désigne celui qui est originaire du village de Kerrien (29), de Kérien (22), ou encore de Querrien (29, également hameau à La Prenessaye, 22). On trouve les racines ker (= village, hameau) et Rien (nom de personne, diminutif du vieux breton ri = roi). Kerrien a été également utilisé comme nom de personne : il existe un saint Kerian, compagnon de saint Ké (ou saint Kay), qui aurait été enterré à Cléder. Keruzoré : Désigne celui qui est originaire du hameau de Keruzoré à Saint-Servais (29). On trouve également Keruzoret à Plouvorn et Ploumoguer. Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Buzoré, nom de personne formé sur les racines bud (= victoire) et uuzoret (= secours) ou uuere (= élevé). Kervella : Originaire de Kervella, l'un des nombreux noms bretons formés à partir de la racine ker (= village, hameau). Kervella est un nom de village assez fréquent dans le Finistère. Vella correspond à la racine gwellan (= meilleur). Kervoern : Rencontré en Bretagne (22, 29), désigne celui qui est originaire d'une localité appelée Kervoern (ker = hameau + voern, sans doute vern = l'aulne). On trouve des hameaux appelés Kervoern à Ploubezre et Trédarzec (22), mais il y a aussi beaucoup de lieux-dits Kervern, qui ont le même sens. Leydecker, Leydekkers : Sans doute flamand, le nom renvoie au néerlandais Leyendecker, qui correspond au métier de couvreur en ardoises. Kervizic : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervizic, hameau de la commune de Kerlouan (29). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Buzic, ancien nom de personne breton, diminutif de bud (= victoire). Kerboul : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerboul, nom de hameaux à Combrit et à Esquibien (29). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de la mare (poull). Variante : Kerboull. Kerjean : Nom porté dans le Finistère (variantes Kerjan, Kerjouan, Kerjoan et Kerjoant dans le Morbihan). Désigne celui qui est originaire d'un hameau appelé Kerjean (= le hameau de Jean), toponyme très répandu en Bretagne (plus de cent hameaux !). Kerr : Nom porté en Grande-Bretagne, notamment en Ecosse, rencontré aussi sous les formes Carr et Ker. Désigne celui qui habite un lieu-dit Kerr. Sens du toponyme : lieu broussailleux et marécageux (vieux scandinave kjarr). Kerbaol : Désigne celui qui habite Kerbaol, nom de quatre hameaux du Finistère, à Plourin, Poullaouen, Saint-Urbain et Plourin-lès-Morlaix. Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Paol (= Paul). Variantes : Kerbaul, Kerbol, Kerboul, Kerboull. Pour ces dernières formes, notons qu'il y a des hameaux appelés Kerboul à Esquibien et à Combrit (29). D'autres hameaux se nomment Kerbol, dans les Côtes-d'Armor et le Morbihan. Kermabon : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kermabon, nom de treize hameaux bretons, dont sept dans le Finistère. Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Mabon, un ancien nom de personne de sens obscur, rencontré dans la mythologie galloise et les chansons de geste. On en fait parfois le cas-régime de mab (= fils). Kerautret : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui habite un lieu-dit Kerautret, le hameau d'Autret. Le toponyme est très répandu dans le Finistère (une bonne vingtaine de mentions). Variante : Kerotret. Autret est un ancien nom de personne, peut-être *Altret (racines alt = allié et ret = utile, selon Albert Deshayes), peut-être diminutif de Auter, nom de personne d'origine germanique (voir Authier). On le retrouve dans le nom de famille Abautret (= le fils d'Autret). Kerckx : Forme génitive de Kerck, qui correspond au néerlandais kerk (= église). Soit celui qui habite près de l'église, soit celui qui travaille pour l'église. Kervarec : Nom surtout porté dans le Finistère. Variantes : Kervarrec, Kervarech (56, 29). Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervarec, nom d'un hameau à Quistinic (56), mais surtout de Kermarec (le m s'étant transformé en v, peut-être par attraction du mot varech), nom d'une bonne vingtaine de hameaux. Signification : le hameau (ker) de Marrec, ancien nom de personne auyant le sens de cavalier (dérivé de marc'h = cheval). Kerguelen : Kerguelen ou Kerguélen est un toponyme très répandu en Bretagne. Si le premier élément (ker) ne pose aucune problème (= hameau), le second peut être interprété de deux façons : il semble désigner le houx (kelenn), mais il faut aussi penser à un nom de personne, Quélian (à rapprocher sans doute de l'irlandais Killian). Variante : Kerguélin. Kerling : Malgré ses allures germaniques et la présence d'une commune appelée Kerling en Moselle, c'est un nom breton désignant celui qui est originaire de Kerling, hameau à Plozévet, dans le Finistère. Le toponyme est formé sur le mot ker (= hameau), le second élément étant plus obscur. Keromnes : Ou Keromnès. Comme pour la plupart des noms bretons commençant par ker-, il s'agit d'un toponyme (ker = hameau), en l'occurrence le hameau d'Omnès (voir ce nom). Il existe une bonne dizaine de hameaux appelés Keromnès, tous dans le Finistère. Kergosien : Surtout porté dans le Morbihan, le nom désigne le hameau (ker) de Gosien, équivalent de Gouzien (ancien nom de personne formé sur la racine uuoed = cri de guerre). Variante : Kergozien. Kerloegan : Nom porté dans le Finistère, où l'on trouve la forme voisine Kerloeguen. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerloeguen, hameau à Pluguffan (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Gloaguen, nom de personne breton (gloeu = clair, brillant + ken = beau). Kerfontain : Porté dans le Morbihan et la Loire-Atlantique, désigne celui qui habite Kerfontaine, nom de plusieurs hameaux bretons (= le hameau de la fontaine, de la source). Variante rare : Kerfontan. Kerouerts : Le nom, très rare, se rencontre en Normandie mais semble d'origine bretonne. Ce devrait être une variante de Kerouartz, désignant celui qui est originaire du village du même nom (commune de Lannilis, 29). Kerzerho : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerzerho, nom de deux hameaux du Morbihan, à Erdeven et à Languidic. Variantes : Kerzéro, Kerzreho, Kerserho. C'est un toponyme formé sur le breton ker (= hameau), le second élément étant plus obscur : A. Deshayes propose un éventuel nom de personne dérivé de serc'h (= amour). Kermagoret : Porté dans le Finistère et le Morbihan, désigne celui qui habite Kermagoret, autrement dit le hameau (ker) fortifié, entouré de murailles (magorec). Kermagoret est le nom d'un hameau à Mellac (29). Kerbarh : Nom porté dans le Morbihan. Variantes : Kerbach, Kerbah, Kerbart. Désigne celui qui habite Kerbarh (ou formes voisines), nom de plusieurs hameaux du Morbihan. Signification : le hameau (ker) de (Le) Barh (voir Le Bars). Kerloc'h : Plus courant sous la forme Kerloch, le nom est porté dans le Finistère. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerloc'h, nom de très nombreux hameaux bretons. Signification : le hameau du lac, de l'étang. Kerdudo : Le nom est surtout porté dans le Morbihan. Variante : Kerdudou. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerdudo, nom d'un château à Guidel (56), ou de Kerdudou, hameaux au Faouët (56) ou à Collorec et Locunolé (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Tudo, ancien nom de personne breton (racine tud = peuple). Kergoat : Assez fréquent dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kergoat, le hameau du bois (ker + coat), toponyme très fréquent en Bretagne. Variantes : Kergoët (22), Kergouet (56). Kerfanto : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerfanto, un toponyme que l'on rencontre sous la forme Kerfantot, ferme ruinée à Saint-Thuriau (56). La forme voisine Kerfant (variante Kerfante) renvoie pour sa part à des hameaux des Côtes-d'Armor, à Lanmérin et Pommerit-le-Vicomte. Le premier élément (ker) signifie 'hameau', le second est plus obscur. Kerdranvat : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire d'un ancien hameau appelé Kerdranvat (ou Kerdravant). Aucune idée sur la localisation de ce toponyme, ni sur le sens de Dranvat. Par contre, ker = hameau, c'est la seule certitude ! Kerneis : Fréquent dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerneiz, Kerneis, nom de divers hameaux de ce département. Sens incertain : le 'hameau du nid' (breton neizh) ne veut pas dire grand-chose. Neis pourrait être ici un nom de personne. Kermarrec : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kermarrec (= le hameau de Marrec, voir ce nom), nom de divers hameaux bretons. Le patronyme est surtout porté dans le Finistère. Variantes : Kermarec, Kermarc. Voir aussi Kervarec. Kerambrun : Porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, désigne celui qui est originaire d'un hameau appelé Kerbrun (ker = hameau + An Brun = Le Brun), toponyme assez fréquent dans ce département. Keramoal : Rare et porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, désigne celui qui habite le hameau (ker) de An Moal (= Le Moal, le chauve). Variante : Kermoal. Keraudren : Fréquent dans le Finistère, c'est un toponyme fréquent en Bretagne (= le hameau d'Audren, voir ce nom). Avec le même sens : Keraudran (56). Kerchrom, Kerc'hrom : Porté dans le Finistère, devrait désigner celui qui est originaire de Kerchrom, hameau à Combrit (29). Signification : le hameau de celui qui s'appelle (Le) Crom (= celui qui est bossu, courbé). Kerhervé : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui habite un hameau appelé Kerhervé (le hameau d'Hervé, ker = hameau), toponyme très répandu dans ce département. Kerébel : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerébel, hameau à Guipronvel (29). Le terme "ker" signifie "hameau". Quant à "-ébel", c'est un surnom correspondant au breton "ebeul" (= poulain)." Kerfriden : Porté dans le Finistère, le nom s'écrit aussi Kerfrident, Kerfridin. Il désigne celui qui habite Kerfriden, hameau à Trégoat (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Friden, Fridin, sans doute nom de personne d'origine germanique formé sur la racine frid (= paix). Kerglonou : Nom breton désignant celui qui habite un hameau ainsi nommé (il en existe à Plouarzel et à Ploumoguer, dans le Finistère). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Glonou, sans doute nom de personne médiéval (Deshayes y voit un ancien Clutgnou, formé sur les racines clut = gloire et gnou = connu). Kergourlay : Nom breton renvoyant à Kergorlay, ancien fief situé à Motreff (29). Le nom de famille est aussi écrit Kergoulay (à noter également le nom noble de Kergorlay). Le toponyme désigne le hameau (ker) de Gourlay (voir Gourlet). Kerisit, Kérisit : Porté dans le Finistère, le nom correspond au breton kerizid, variante de kerezeg (= cerisaie). De nombreux hameaux ou lieux-dits du Finistère s'appellent Kérésit, Kérisit. Kermaïdic : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kermaidic, hameau à Plourin-Ploudalmézeau (29). Le mot "ker" signifie "hameau", le second élément étant sans doute un ancien nom de personne." Kermorgant : Porté dans le Finistère, devrait désigner celui qui est originaire de Kermorgant, hameau au Cloître-Saint-Thégonnec (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Morgant (nom de personne similaire à Morgan, voir ce nom). Kerurien : Porté dans les Côtes d'Armor, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerurien, hameau à Grâces (22). Signification du toponyme : le hameau (ker) d'Urien (voir ce nom). Kernévez : Porté dans le Finistère, le nom s'écrit aussi Kernévès. Il signifie "le nouveau hameau, le nouveau village", toponyme fréquent en Bretagne. Avec le même sens : Kernévé (56), Kernével (29)." Kerriguy : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerriguy, hameau à Daoulas (29). Variante : Kériguy (graphie erronée : Kérigny). Signification lieu rocheux (breton karrigi, kerrigi). Kersaho : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerserho, hameau à Languidic (56). Variantes : Kerserho, Kerzerho, Kerzero, Kerzreho. Le premier élément du nom signifie hameau, village, le second étant selon A. Deshayes un ancien nom de personne, *Serc'hou, diminutif de serc'h (= amour). Kervahu : Egalement écrit Kervahut, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervahut, hameau à Plonéour-Lanvern (29). Kervéadou : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervéadou, nom de hameaux à Baye, Rédené et Tréméven (29). Signification : le hameau, le village (ker) de *Béadou, sans doute nom de personne formé sur le latin beatus (= heureux), selon A. Deshayes. Avec le même sens : Kervédaou, Kervédou. Kerveillant : Egalement écrit Kervaillant, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerveillant (ou Kervaillant), nom de divers hameaux bretons. Signification : le hameau (ker) de Vaillant (voir ce nom). Kerf : Nom très rare porté dans le Nord, un peu plus fréquent en Belgique, de sens incertain. Il a pu désigner un balafré (moyen néerlandais kerf = entaille). Avec génitif de filiation : Kerfs. Kerhrom : Le nom est porté dans le Finistère. Egalement écrit Kerhom, c'est une variante de Kerchrom (voir ce nom). Kersauzon (de) : Ou Kersauson. Le nom, surtout porté dans le Finistère, renvoie à une localité du même nom. On pensera surtout à Kersauzon, dans la commune de Sibiril (29), d'autres hameaux portant cependant le même nom dans le Finistère et les Côtes-d'Armor. Signification : le hameau, le village (ker) de Sauzon (= le Saxon). Kervévan : Le nom est surtout porté dans le Finistère. Variantes : Kervévant, Kervéven. Il désigne celui qui est originaire du hameau de Kervévan à Meilars (29). Signification du toponyme : le hameau, le village (ker) de Bévan (voir ce nom). Kerenfors : Rare, le nom est porté dans le Finistère et la Loire-Atlantique. Variante : Kerenfort. Forme ancienne : Keranfors. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Keranfors, Kerenfors, nom de hameaux ou de fermes à Guimiliau, Plougonvern et Plouigneau (29). Le terme "ker" a le sens de "hameau, village". On trouve ensuite l'article "an" (= "le"), le dernier élément étant obscur : on peut éventuellement penser à l'adjectif français "fort", ou encore à l'ancien français "force" (= forteresse)." Kerbrat : Assez fréquent dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de l'un des nombreux hameaux ou lieux-dits appelés Kerbrat dans ce département. Signification : le hameau, le village (ker) du pré (prat). Kerignard : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerignard, hameau à Sarzeau (56). Signification du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Hignard (voir ce nom). Kervoal : Le nom est porté dans le Finistère. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervoal, nom de hameaux ou de fermes à Beuzec-Cap-Sizun, Huelgoat, Meilars, Poullan-sur-Mer et Treouergat, toutes ces communes se trouvant dans le Finistère. Autre hameau à Elven (56). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Rivoal (voir ce nom). Kervoalen : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervoalen, nom de hameaux à Garlan, Plovan et Rosnoen (29), ainsi qu'au Vieux-Marché (22). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Goalen (voir ce nom). Kerduel : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerduel, nom de hameaux bretons à Moelan-sur-Mer (29), Lignol et Plouay (56). A noter aussi le château de Kerduel à Pleumeur-Bodou (22). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Tuel, ancien nom de personne (voir Tual). Kervinio : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervinio, hameaux à Lanvaudan, Ploemeur et La Trinité-sur-Mer (56). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Guinio, nom de personne également présent en Morbihan. Kerbouët : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne peut-être celui qui est originaire de Kerbouër, hameau à Lanvenegen (56). Signification : le hameau (ker) de celui qui s'appelle Bouer, Le Bouer (= le sourd, variante de "bouzar")." Kergustan : Nom porté dans le Morbihan. Autres formes : Kergustanc, Kergustant. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kergustanc, hameau à Locmalo (56), éventuellement de Kergustans à Plomodiern (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) de Gustan (nom de personne qui pourrait correspondre à Justin ?). Keryel : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Keryel, nom de divers hameaux bretons : à Plougonvelin, Plounéour-Menez et Tréglonou (29), ainsi qu'à Kervignac (56). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Rihael, nom de personne breton mentionné dans le cartulaire de Redon. Avec le même sens : Keriel, Kerriel, Keryell (d'autres hameaux s'appellent Keriel ou Kerriel). Kercret : Porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kercret, nom de deux hameaux à Ploemel (56) : Kercret-Ihuel et Kercret-Izel (Kercret d'en haut et Kercret d'en bas). Le premier élément du nom (ker) signifie "hameau", le second est assez obscur. Il faut sans doute y voir le breton "kred" (= caution, confiance), peut-être utilisé comme nom de personne." Kerambellec : Désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerambellec, nom de dix-huit hameaux bretons situés dans le Finistère ou les Côtes d'Armor. Signification du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de celui qui s'appelle Le Bellec (en breton An Bellec), autrement dit "le prêtre". Le nom de famille est surtout porté dans les Côtes d'Armor. Variante : Kerembellec." Keradec : Rare et porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Keradec, nom de trois hameaux de ce département : à Commana, Plourin et Kersaint-Plabennec. Si l'élément "ker" signifie hameau, l'ensemble du nom est plus obscur (le mot breton "hadeg" signifie "semis", c'est une solution éventuelle)." Keradennec : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerradennec, Kerradénec, nom de près d'une trentaine de hameaux ou de fermes, pour la plupart dans le Finistère. Signification : le hameau (ker) de la fougeraie (radeneg). Keraël, Kerael : Rare et porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Keraël, nom de dix-huit hameaux ou fermes situés pour la plupart dans le Finistère, parfois dans les Côtes-d'Armor. Signification : le hameau (ker) de Haël, ancien nom de personne ("hael" = noble, magnanime)." Keraën : Egalement écrit Kérain, Kerraën, Kerrain, le nom est porté dans le Finistère. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Keraën, hameau à Saint-Thois (29), ou de Kerrain à Scrignac (29) et à Plumergat (56). Si le mot "ker" signifie "hameau", le second élément est plus incertain. A. Deshayes le rapproche du mot gallois "rhain" (= raide)." Kerallan : Porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerallan, nom d'une douzaine de hameaux ou fermes bretons. Signification : soit le hameau (ker) d'Allan (voir ce nom), soit le hameau de la lande ("an lann"), A. Deshayes signalant que plusieurs de ces lieux sont notés Keranlan dans les documents anciens." Keramanach : Ou Keramanac'h. Porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, désigne celui qui est originaire de Keramanac'h, hameaux à Plounévez-Moëdec (22), à Lanneuffret et Taulé (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) du moine ("an manac'h"), ou de celui qui s'appelle Le Manach, Le Manac'h. Avec le même sens, les formes Kermanach, Kermanac'h (29) renvoient à une dizaine de hameaux ainsi appelés (22, 29). Autre variante : Kermanec (22)." Kerambloch : Ou Kerambloc'h. Le nom est porté dans le Finistère. Il désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerambloc'h, nom de deux hameaux à Loc-Eguiner-Saint-Thégonnec et à Sizun (29). On pensera aussi à Keramblouc'h, autre hameau à Trézény (22). Signification : le hameau de celui qui s'appelle Le Bloch (breton "bloc'h" = entier ou glabre)." Keramborgne : Porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, devrait désigner celui qui est originaire de Keramborgne, hameau à Trégunc (29), ou de Keramborn, nom de trois hameaux à Loguivy-Plougras, Le Vieux-Marché (22) et Plounéour-Ménez (29). Signification : le hameau (ker) du borgne (breton "an born")." Kerdavid : Surtout porté dans le Morbihan, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerdavid, nom d'une quarantaine de hameaux bretons. Signification : le hameau (ker) de David, nom de personne. Kerdelhué : Surtout porté dans le Morbihan, devrait désigner celui qui est originaire de Kerdalhué, hameau à Guidel (56). Signification : le hameau (ker) situé sur une hauteur (breton "al laez")." Kerviche : Surtout porté dans le Morbihan, c'est un nom que les plus anciennes mentions connues situent à Ambon (56) depuis le XVIe siècle. Il désigne celui qui est originaire d'un lieu ainsi appelé (ker = hameau). On peut certes faire le rapprochement avec Kervich, hameau à Plougonver (22), mais celui est bien loin de la région concernée. On trouve par contre dans le Morbihan pas mal de hameaux appelés Kerbic ou Kervic, par exemple Kervic à Locmaria. C'est une solution géographiquement plus séduisante, mais douteuse du point de vue phonétique. Kermorvant : Porté dans le Morbihan, peut désigner celui qui est originaire de Kermorvant, hameau à Moustoir-Ac (56), ou encore de Kermorvan, nom de plusieurs dizaine de hameaux bretons. Signification : le hameau (ker) de Morvan (voir ce nom). Variantes : Kermorvan, Kermovant. Kerourédan : Surtout porté dans le Finistère, désigne celui qui est originaire de Kerourédan, hameau à Quéménéven (29), ou encore de Kerorédan à Plogonnec (29). Sens du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Uuoretan, nom de personne plusieurs fois cité dans le cartulaire de Redon. Kervazo : Porté dans le Morbihan (variante rare : Kervaso), désigne celui qui est originaire de Kervazo, nom de divers hameaux de ce département : à Brech, à Limerzel, à Locoal-Mendon, à Malguénac et à Priziac. Le premier élément ("ker") a le sens de village, hameau. Le second, plus incertain, pourrait être un diminutif de "gwazh" (= ruisseau). Kerlau : Porté dans le Morbihan (variante : Kerlaud), devrait désigner celui qui est originaire de Kerlau, hameau à Pont-Scorff (56). On trouve un autre hameau du même nom à Callac (22). Le premier élément (ker) signifie "hameau, village", le second, selon A. Deshayes (voir bibliographie) correspond au nom de personne breton Hellou." Kerphérique : Porté dans les Côtes-d'Armor, le nom s'écrit aussi Kerphirique, Kerfuric. C'est un toponyme commençant par "ker" (= hameau, village), suivi du nom de personne Furic, sans doute diminutif de "fur" (= sage). A noter cependant que le mot "furik" désigne le furet. Reste à situer ce lieu. Peut-être s'agit-il de Kerfury à Merléac (22). Le nom de famille Kerfury existe aussi dans le même département. " Kerouault : Porté dans le Morbihan (variante : Kerrouault), désigne celui qui habite un lieu-dit Kerrouault, le hameau (ker) de Rouault (voir ce nom). Pour le Morbihan, il s'agit sans doute de Kerrouault à Férel, mais deux hameaux portent aussi ce nom dans les Côtes-d'Armor : à Plerneuf et à Saint-Gilles-Vieux-Marché. Kerry : Le nom Kerry est anglais, c'est une variante de Kendrick, correspondant à l'ancien nom de personne Cenric, formé des racines "cyne" (= royal) et "ric" (= puissant). Concernant John Kerry, il convient cependant de préciser que ses ancêtres, qui vivaient en Tchécoslovaquie, s'appelaient Kohn (diminutif de Konrad), et que sa famille a changé de nom au début du XXe siècle." Kerdaffrec : Porté dans le Finistère, le nom peut aussi s'écrire Kerdaffré, Kerdaffret. Il désigne celui qui habite un lieu-dit Kerdaffret, nom d'un ancien hameau à Spézet (29), écrit Kerdafroc sur la carte de Cassini. Le premier élément ("ker") a le sens de "hameau". Le second, selon A. Deshayes (voir bibliographie) paraît correspondre au qualificatif gallois "dyfryd" (= triste)." Kerdoncuff : Nom breton désignant celui qui est originaire de Kerdoncuff, nom de deux hameaux ou fermes à Bodilis et à Poullaouen, dans le Finistère (autre possibilité : Keroncuff, hameau à Dirinon). Variantes : Keroncuf, Kerzoncuf, Kerzoncuff. Signification du toponyme : le hameau (ker) de Doncuff, probable variante de Dencuff, nom de personne ou surnom (den = homme + cuff = doux). Kerforn : Nom breton également écrit Kerforne, Kerfourn. Il désigne celui qui habite un lieu-dit Kerforn, toponyme fréquent signifiant "le hameau (ker) du four (forn)". Avec le même sens : Keranforn, où "forn" est précédé de l'article défini "an"." ConclusionLe terme "ker" est ainsi profondément ancré dans l'identité bretonne, omniprésent dans sa toponymie et son anthroponymie. Plus qu'un simple élément linguistique, il incarne le patrimoine culturel de la région et témoigne de la vitalité de la langue bretonne, dont l'influence se perpétue à travers les innombrables noms de lieux et de famille qui en sont issus. Déchiffrer la signification des toponymes et patronymes en "Ker-", c'est plonger au cœur de l'histoire et de la géographie bretonnes, et rendre hommage à la richesse d'une culture toujours vivante.

1 Comment

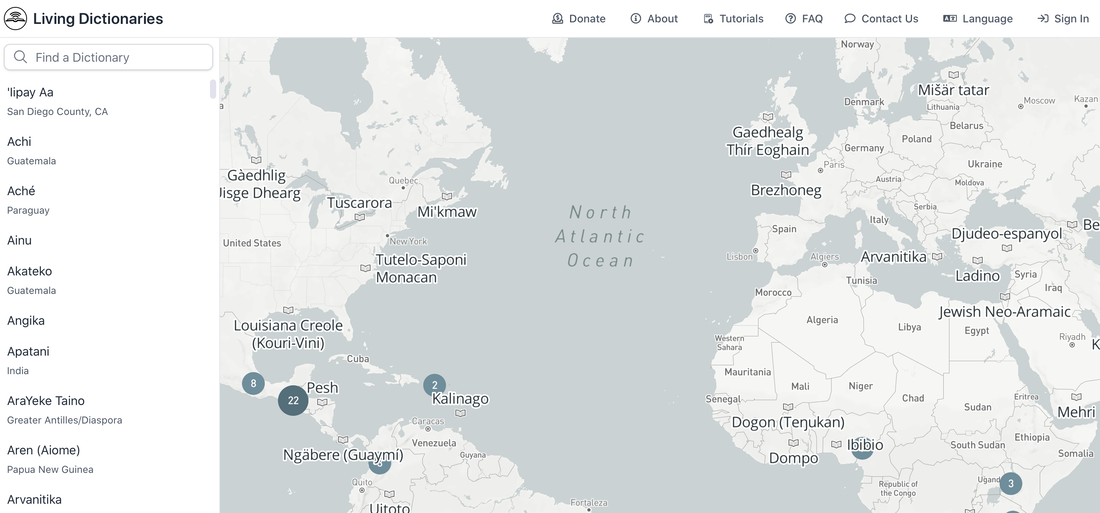

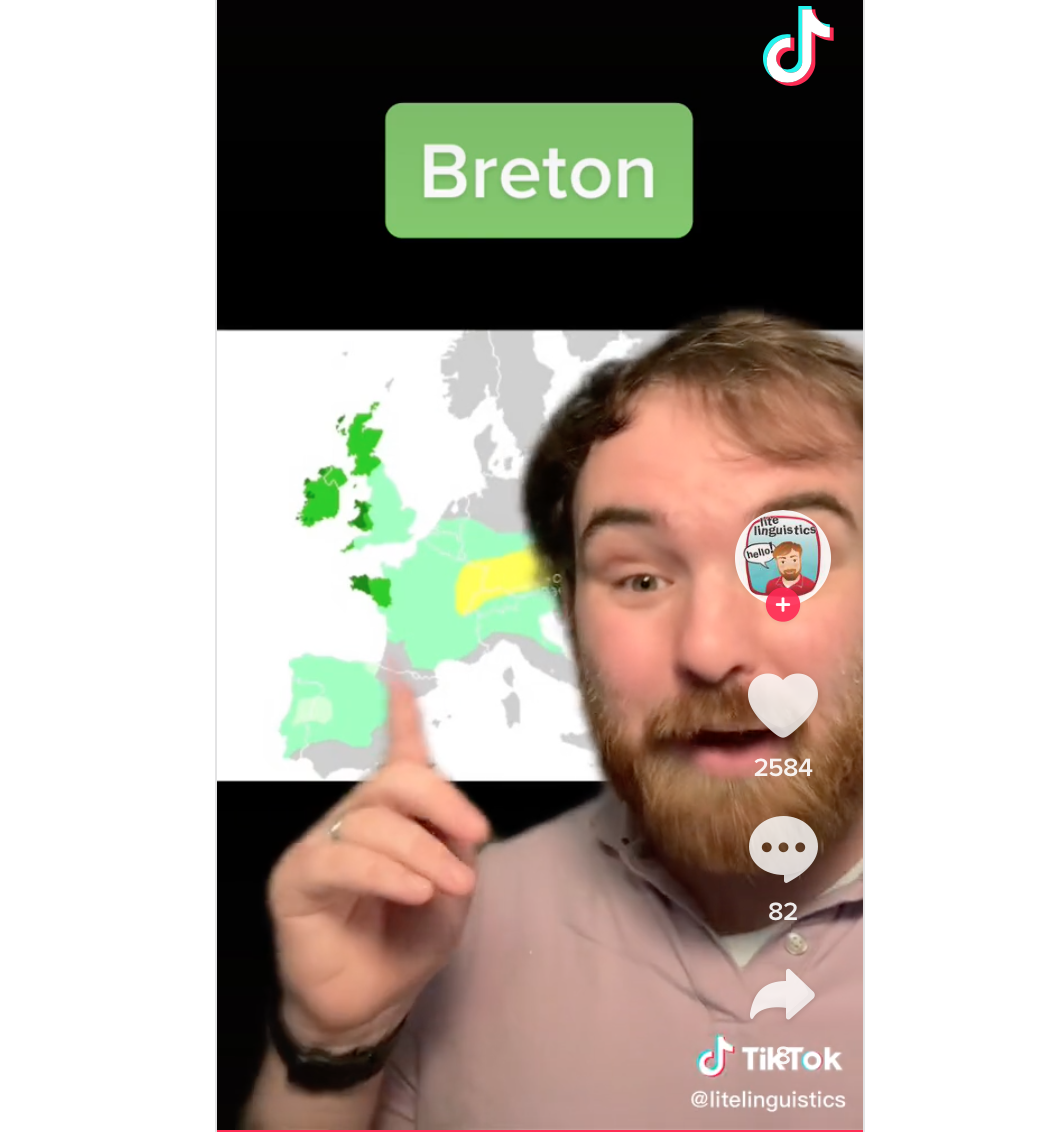

Les noms de lieux bretonsLa Bretagne, région riche en histoire et en culture, possède un patrimoine linguistique unique qui se reflète dans sa toponymie. Les noms de lieux bretons, façonnés au fil des siècles par la langue bretonne, témoignent de l'identité profonde de la région. Ils décrivent les paysages, les particularités géographiques, les constructions humaines et les croyances anciennes, offrant ainsi un véritable voyage dans le temps et dans l'espace. Comprendre la signification des noms de lieux bretons, c'est plonger au cœur de l'âme bretonne. Chaque toponyme raconte une histoire, évoque un passé lointain et nous connecte à la terre et à ceux qui l'ont façonnée. Cet héritage linguistique, fruit de la rencontre entre la langue bretonne et le territoire, est un trésor inestimable qu'il est crucial de préserver et de transmettre aux générations futures. Dans cet article, nous explorerons les origines des noms de lieux bretons, leur signification profonde et les menaces qui pèsent sur ce patrimoine fragile. Nous découvrirons comment la langue bretonne a imprégné la toponymie régionale et nous nous pencherons sur les initiatives mises en place pour sauvegarder cet héritage linguistique unique. Un voyage passionnant au cœur de l'identité bretonne, à travers les mots qui ont façonné son territoire. Les origines des noms de lieux bretonsLa toponymie bretonne a été profondément marquée par l'immigration de Bretons de Grande-Bretagne aux Ve et VIe siècles. Cette vague migratoire, causée principalement par l'invasion saxonne à partir de 450, mais aussi par les raids des Pictes et des Scots sur les côtes ouest de l'île dès la fin du IIIe siècle, a entraîné la création de nombreux nouveaux noms de lieux et l'évolution des toponymes antérieurs dans un contexte breton. Ainsi, le territoire des Osismes fut renommé Cornouaille, un nom qui, sous sa forme française, est d'origine latine (Cornu Gallia, le coin de la Gaule), mais qui, sous sa forme bretonne Kerne, est relié au nom des Cornovii du Cornwall de Grande-Bretagne. De même, le nord des cités des Osismes et des Curiosolites forma une entité nommée Domnonée, un nom identique à celui d'une région de Grande-Bretagne qui a donné le nom du Devon. L'ancien nom de la (Grande-) Bretagne, Preden, est resté dans des toponymes comme Rosporden et Trebeurden. Les liens entre le breton, le gallois et le cornique, langues brittoniques partageant une origine commune, se reflètent dans la toponymie de ces régions. Les noms en Lan-, se rattachant à des fondations monastiques, trouvent leurs équivalents au pays de Galles, comme à Langolen (29) et son homonyme gallois Llangollen, avec un saint Gollen dont on ne sait quasiment rien. Les noms en Tre(b)-, mot proche du latin Tribus, ont aussi leurs pendants en Grande-Bretagne. Si la présence de Bretons sur le continent est notoire dès la fin du IVe siècle, dans la péninsule armoricaine, elle n'est attestée de manière certaine qu'au début du VIe siècle. Cette immigration a profondément changé la toponymie de la région, en créant de nouveaux noms de lieux et en faisant évoluer les noms antérieurs dans un contexte breton. La parenté linguistique entre le breton, le gallois et le cornique témoigne de l'héritage culturel partagé entre la Bretagne, le pays de Galles et les Cornouailles. Elle souligne l'importance des échanges et des migrations de populations brittoniques dans la formation de l'identité et de la toponymie de ces régions. La signification des noms de lieux bretonsLa toponymie bretonne est riche en termes récurrents qui, associés les uns aux autres, permettent de former des noms de lieux très descriptifs. Parmi ces termes, "Ker" est sans doute le plus fréquent. Signifiant "village", "lieu habité" ou "hameau". On le retrouve par exemple dans "Kermorvan" (village de Morvan), "Kerbrat" (village du pré) ou encore "Kerlouan" (village de Saint Louan). D'autres termes fréquents incluent "Lan" (ermitage, lieu sacré), comme dans "Landévennec" (ermitage de Saint Gwenneg), "Loc" (lieu saint, ermitage), présent dans "Locronan" (ermitage de Saint Ronan), ou encore "Pen" (tête, bout, cap), que l'on retrouve dans "Penmarc'h" (tête de cheval) ou "Penmarch" (bout du champ). Comprendre ces termes récurrents est essentiel pour appréhender la signification des noms de lieux bretons et percevoir la manière dont la langue décrit le territoire. Les toponymes liés aux éléments naturels (relief, cours d'eau, végétation)La Bretagne, riche en éléments naturels, voit son paysage immortalisé à travers ses toponymes, décrivant le relief, les cours d'eau et la végétation environnants. - Alez : Alez Brenn (allée de la colline), Alez Kamm (ancienne route tortueuse) - Bod/bot/bos/bou/vod/bo : Bodilis (maison de Lis), Botjaffré (demeure de Geoffroy), Bosdel (demeure de Del) - Gwern/guern/wern/vern/guer/ver : Guern (lieu marécageux), Kervignac (village de l'aulnaie), Penvern (sommet de l'aulnaie) - Hinec : Plouhinec (paroisse de l'ajonc), Guérande (partiellement en Bretagne) (village de l'ajonc), Méviane (ajonc noir) - Ivin/ivinenn/ignel/vign : Kerivin (village aux ifs), Inguiniel (village aux ifs), Yvignac (lieu planté d'ifs) - Koad/coat/goat/koed/C'hoed/goet/gouet : Coat-Losquet (bois brûlé), Koad an Noz (bois de la nuit), Goas- ar-Foen (bois du ruisseau) - Linad : Bolénat (touffe d'orties), Boulinat (touffe d'orties), Lenadec (touffe d'orties) - Raden : Bodraden (buisson de fougères), Radenec (lieu de fougères), Enez Raden (île de la fougère) - Rest : Resto (lieu de repos), Kerrestou (lieu de repos), Restermouel (demeure d'Armel) Les toponymes liés aux constructions humaines (villages, fermes, édifices religieux)L'empreinte de l'homme dans le paysage breton se manifeste à travers ses toponymes, qui décrivent villages, fermes et édifices religieux. - Kêr/'gêr/car et formes francisées quer/guer : Kermoroc'h (village au grand promontoire), Kerbors (village du tourbeux), Kerfréhour (village du marchand de fruits) - Iliz/ilis : Bodilis (église de Lis), Brennilis (église de Nil), Kernilis (église de Nil) - Tavarn : Tavarn (taverne), Tavarnou (petite taverne), Tavarn-Plouénan (taverne de Plouénan) - Tre/trev/tref : Trédaniel (village de Daniel), Trégarantec (village du saint Garantec), Trégastel (village de la lande) - Ty/thi/thy/ti : Ty Névez (nouvelle maison), Tizoul (maison au toit de chaume), Ty Losquet (maison brûlée) - Leur/lor : Leurangue (aire à battre le grain), Loranguer (aire à battre le grain), Leslor (aire à battre le grain) - Lez/li : Lézardrieux (lieu de lisière), Lesconil (lieu de lisière), Lesneven (lieu de lisière) - Leti : Leti (auberge), Letty (maison du lait), Letiau (auberge) - Minic'hi : Minihy-Tréguier (asile de Tréguier), Minihy du Léon (asile du Léon), Minihy (asile) - Kure : Kambr ar C'hure (maison du vicaire), Coat ar c'hure (bois du vicaire), Kureb (ferme du vicaire) Les toponymes liés aux personnages historiques et aux saints bretonsL'histoire et la tradition religieuse de la Bretagne sont ancrées dans ses toponymes, honorant des personnages historiques et des saints locaux. - Lan : Landivisiau (ermitage de saint Thivisiau), Lamballe (ermitage de Paul), Laurenan (ermitage de Ronan) - Plou-/plo/ple/pla/pleu/plu/ploe/pleb : Plougonvelin (paroisse du gué), Plouézec (paroisse d'Erseka), Plouay (paroisse de Kay) - Menec'h : Menec'h-ty (maison des moines), Manac'h-ti (maison du moine), Keramanac'h (hameau du moine) - Kroaz/croaz/groez/greiz/greis/creis : Le Croisic (la petite croix), Kergroix (village de la croix), Creisker (centre-ville) - Kastell : Castel Du (château noir), Kastellin (petit château), Châteaulin (château du lin) - Lok/loc/log : Locolven (lieu saint de Goulven), Locminé (lieu saint de Neven), Loctudy (lieu saint de Tudy) - Menec'h : Menec'h-ty (maison des moines), Manac'h-ti (maison du moine), Keramanac'h (hameau du moine) - Plou-/plo/ple/pla/pleu/plu/ploe/pleb : Plougonvelin (paroisse du gué), Plouézec (paroisse d'Erseka), Plouay (paroisse de Kay) - Tre/trev/tref : Trédaniel Les menaces pesant sur les noms de lieux bretonsMalgré leur richesse et leur importance, les noms de lieux bretons sont aujourd'hui menacés. La francisation des toponymes, entamée dès le XVIe siècle, a conduit à la déformation ou à la traduction de nombreux noms de lieux, rendant leur signification originelle opaque. L'urbanisation et la standardisation des noms de rues et de quartiers contribuent également à effacer la mémoire des lieux. Les noms bretons, jugés difficiles à prononcer ou à écrire, sont souvent remplacés par des noms français génériques, sans lien avec l'histoire ou la géographie locales. Enfin, la perte de la pratique de la langue bretonne entraîne un risque d'oubli de la signification des toponymes. Sans transmission, cette richesse linguistique et culturelle pourrait progressivement disparaître. Récemment, la loi 3DS (Différenciation, Décentralisation, Déconcentration et Simplification), adoptée en février 2022, a suscité de vives inquiétudes quant à la préservation de la toponymie bretonne. Cette loi oblige les communes à dénommer les voies et les lieux-dits, à donner un numéro à chaque usager et à fournir l'adressage au format Base Adresse Locale dans la Base adresse nationale. Selon l'association Koun Breizh (Souvenir breton), cet adressage conduit de manière silencieuse à la débretonnisation de nombreux lieux-dits, parfois sans que les élus ne le mesurent. Des règles techniques privilégient les noms de rue et prennent le pas sur une toponymie ancestrale en langue bretonne, occasionnant une perte inestimable. Dans ce contexte, Koun Breizh a sollicité un moratoire sur l'application de la loi 3DS et a adressé une requête à l'UNESCO afin d'obtenir l'inscription en extrême urgence de la toponymie bretonne sur la liste du patrimoine immatériel nécessitant une sauvegarde urgente. Avec un peu plus de 200 000 locuteurs actifs, dont près de 80% de plus de 60 ans, la langue bretonne est considérée comme gravement menacée par l'UNESCO. Une victoire symbolique pour Plouégat-Guérand : conservation des noms bretonsPlouégat-Guérand, une petite commune du Finistère comptant 1 065 habitants, vient de remporter un combat significatif contre La Poste. Confrontée à la demande de francisation des 140 lieux-dits de la localité, elle a obtenu le droit de conserver leurs appellations d'origine. La Poste, invoquant la loi 3DS, exigeait que les communes de moins de 2 000 habitants nomment toutes leurs rues et numérotent leurs bâtiments avant le 1er janvier 2026, avec des désignations "à la française". Cependant, les élus du conseil municipal de Plouégat-Guérand ont résisté à cette demande. Plutôt que de se plier aux exigences de La Poste, ils ont découvert des alternatives permettant de préserver le caractère patrimonial de nombreux noms, parmi lesquels certains sont très anciens. La solution consiste à utiliser le numéro suivi du nom du lieu-dit, par exemple "1 Keramoal" au lieu de "1 rue de Keramoal". Cette approche permet de maintenir des éléments historiques et culturels importants pour la commune, comme le nom "Blein Maro", signifiant "le loup mort", ancré dans son histoire ancestrale. ConclusionLes noms de lieux bretons constituent un patrimoine linguistique et culturel inestimable, témoin de l'histoire et de l'identité de la Bretagne. Façonnés par la langue bretonne au fil des siècles, ils décrivent avec poésie et précision les paysages, les constructions humaines et les croyances qui ont forgé le territoire breton. Aujourd'hui menacés par la francisation, l'urbanisation et la perte de la pratique du breton, ces toponymes doivent être préservés et valorisés. Les initiatives de collecte, de recherche et de promotion de la toponymie bretonne, portées par des associations, des chercheurs et des collectivités locales, sont essentielles pour maintenir vivante cette richesse linguistique unique. Préserver les noms de lieux bretons, c'est assurer la transmission d'un héritage culturel précieux aux générations futures. C'est aussi permettre à tous, Bretons et visiteurs, de comprendre et d'apprécier la beauté et la profondeur de la langue bretonne, inscrite dans chaque colline, chaque rivière et chaque village de la région. Protéger la toponymie bretonne, c'est finalement œuvrer pour la sauvegarde de la diversité linguistique et culturelle, un enjeu crucial à l'heure de la mondialisation. En célébrant et en chérissant les noms de lieux bretons, nous affirmons notre attachement à une Bretagne fière de ses racines, ouverte sur le monde et résolument tournée vers l'avenir. Brezhoneg Living DictionaryIt's wonderful news for Brittany enthusiasts and cultural preservationist! Breizh Amerika has partnered with the Living Tongues Institute in the USA on an ambitious project to create an online Breton Living Dictionary available in English, French, and Breton languages. UNESCO has stated that the Breton language is severely endangered. This new online dictionary serves as a digital haven, housing hundreds of Breton words and phrases, providing sanctuary not only for the Breton diaspora but also for language learners across the globe seeking to immerse themselves in the richness of Breton linguistic heritage. Living Dictionaries: Beyond Mere Words on a ScreenThe Living Tongues Institute is on a monumental mission—to ensure the survival of endangered languages. Through activism, education, and technology, they bolster communities in safeguarding their languages from extinction. Their approach involves language documentation, digital workshops, and the creation of resources like Living Dictionaries, crucial for language revitalization efforts. Let's talk numbers. The Institute boasts a significant track record: aiding over 100 endangered language communities between 2005 and 2019, along with conducting online workshops for 200+ language activists across 25+ countries from 2020 to 2023. Their aim? To develop 3,000+ Living Dictionaries over the next 30+ years, a testament to their unwavering commitment to language preservation. Breizh Amerika's president, Charles Kergaravat, noticed the absence of a Breton Living Dictionary and reached out to the Institute, proposing to rectify this gap. Brezhoneg's Fight for Survival: Breizh Amerika's EndeavorBreizh Amerika, committed to promoting Breton culture, wholeheartedly dived into this project. They collaborated with Breton speakers like Bernez Rouz and organizations like Dizale to construct and record the Brezhoneg Living Dictionary. With the goal to raise awareness about the severely endangered Breton language and contribute to its revitalization. The Brezhoneg Living Dictionary, available online, dismantles linguistic barriers. This digital tool transcends geographical boundaries, enabling individuals from diverse backgrounds to access and engage with Breton language and culture. With translations and a user-friendly interface, it acts as a conduit for Breton's preservation and growth. Its accessibility empowers language learners, enthusiasts, and researchers, fostering a deeper global understanding and appreciation for the Breton language. Unveiling the Breton Language: Embracing HeritageBreton, as a member of the Celtic language family, holds profound historical and cultural significance within Brittany, France. It stands as a testament to the rich tapestry of European linguistic heritage. However, despite its cultural importance, Breton faces the looming threat of extinction. Grassroots movements and initiatives aim to elevate its visibility and recognition, highlighting its value not just as a language but as a living embodiment of a unique cultural identity. Reviving Breton involves educational programs, cultural events, and community engagement, all vital in ensuring its survival amidst the challenges it confronts. On behalf of the Living Tongues Institute, it has been our pleasure to collaborate with Breizh Amerika on the creation of the Brezhoneg Living Dictionary. A searchable, mobile-friendly tool containing 300+ entries in Brezhoneg with accompanying audio recordings, and translations into English and French, this project will help create visibility and access to the language across the Breton diaspora in Europe and North America. “On a personal note, this project makes me particularly proud, because my great-grandfather Joseph-Marie Gallon was a fluent Breton speaker. An immigrant from northern France to Canada in the early 20th century, he often sang and performed in his mother tongue. Although he never transmitted the language to his children, who grew up speaking French and English, his daughter Cécile Gallon (my grandmother) lovingly recalled him speaking in Breton and always felt a connection to the language. My memory of her affection for it stays with me until this day.” Anna Luisa Daigneault, Program Director, Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. Brezhoneg Living DictionaryC'est une excellente nouvelle pour les passionnés de la Bretagne et les défenseurs de la préservation culturelle ! Breizh Amerika s'est associé à l'Institut des Langues Vivantes aux États-Unis pour un projet ambitieux : créer un Dictionnaire Vivant Breton disponible en ligne, en anglais, en français et en breton. L'UNESCO a déclaré que la langue bretonne est gravement en danger. Ce nouveau dictionnaire en ligne agit comme un refuge numérique, abritant des centaines de mots et de phrases bretons, offrant un sanctuaire non seulement à la diaspora bretonne, mais aussi aux apprenants de langues du monde entier désireux de se plonger dans la richesse du patrimoine linguistique breton. Dictionnaires Vivants : Au-delà de Simples Mots sur un ÉcranPlongeons davantage dans le concept des Dictionnaires Vivants. Ce ne sont pas les dictionnaires imprimés et statiques que l'on connait qui prennent la poussière sur les étagères. Ce sont des outils interactifs et vivants qui vont au-delà des mots, intégrant des enregistrements audio, des images captivantes et des vidéos de locuteurs natifs. Cette expérience immersive vise non seulement à préserver les mots, mais aussi la culture et le patrimoine. L'Institut des Langues Vivantes est engagé dans une mission monumentale : assurer la survie des langues en danger. Grâce à l'activisme, l'éducation et la technologie, il soutient les communautés dans la préservation de leurs langues pour éviter leur extinction. Leur approche inclut la documentation linguistique, les ateliers numériques et la création de ressources comme les Dictionnaires Vivants, cruciaux pour la revitalisation des langues. Parlons chiffres. L'Institut a un bilan remarquable : ils ont aidé plus de 100 communautés linguistiques en danger entre 2005 et 2019, et ont organisé des ateliers en ligne pour plus de 200 militants linguistiques dans 25 pays différents entre 2020 et 2023. Leur objectif ? Développer plus de 3 000 Dictionnaires Vivants au cours des 30 prochaines années, un témoignage de leur engagement indéfectible envers la préservation des langues. Le président de Breizh Amerika, Charles Kergaravat, a remarqué l'absence d'un Dictionnaire Vivant Breton et s'est tourné vers l'Institut pour combler cette lacune. Combat pour la Survie du Brezhoneg : L'Engagement de Breizh AmerikaBreizh Amerika, dévoué à la promotion de la culture bretonne, s'est plongé corps et âme dans ce projet. Ils ont collaboré avec des locuteurs bretons comme Bernez Rouz et des organisations comme Dizale pour créer et enregistrer le Dictionnaire Vivant Brezhoneg. Cette initiative vise à sensibiliser sur le grave danger que court la langue bretonne et à contribuer à sa revitalisation. Le Dictionnaire Vivant Brezhoneg, disponible en ligne, réduit les barrières linguistiques. Cet outil numérique transcende les frontières géographiques, permettant à des individus de divers horizons d'accéder et d'explorer la langue et la culture bretonnes. Avec des traductions et une interface conviviale, il agit comme un vecteur de préservation et de développement du breton. Son accessibilité autonomise les apprenants en langues, les passionnés et les chercheurs, favorisant une compréhension et une appréciation plus profondes de la langue bretonne à l'échelle mondiale. "J'ai enregistré des centaines de mots en breton prononcés par Bernez Rouz. Ce projet permet de faire un dictionnaire sonore des mots en breton. D'habitude, j'enregistre et je mixe des doublages en breton de films et de dessins-animés dans ce studio, utilisé par Dizale à Quimper. Ce projet nous a permis de rencontrer les personnes travaillant à l'institut Living Tongues et leur faire découvrir notre langue, notre travail et nos compétences sur le travail du son.", Jean Mari Ollivier de Dizale. Dévoiler la Langue BretonneLe breton, en tant que membre de la famille des langues celtiques, détient une importance historique et culturelle profonde en Bretagne, en France. Il témoigne de la richesse du patrimoine linguistique européen. Cependant, malgré son importance culturelle, le breton est confronté à la menace imminente de l'extinction. Des mouvements populaires et des initiatives visent à accroître sa visibilité et sa reconnaissance, soulignant sa valeur en tant que langue mais aussi en tant qu'incarnation vivante d'une identité culturelle unique. La revitalisation du breton implique des programmes éducatifs, des événements culturels et aussi une implication de la diaspora, tous essentiels pour garantir sa survie face aux défis qu'il affronte. “Au nom de l'Institut Living Tongues, nous avons eu le plaisir de collaborer avec Breizh Amerika à la création du Dictionnaire vivant brezhoneg. Cet outil, qui est consultable et adapté aux téléphones portables, contient plus de 300 entrées en brezhoneg, accompagnées d'enregistrements audio et de traductions en anglais et en français. Ce projet contribuera à la visibilité et à l'accès à la langue au sein de la diaspora bretonne en Europe et en Amérique du Nord. D'un point de vue personnel, ce projet me rend particulièrement fière, car mon arrière-grand-père Joseph-Marie Gallon parlait couramment le breton. Un immigré du nord de la France au Canada au début du 20e siècle, il chantait et jouait souvent dans sa langue maternelle. Bien qu'il n'ait jamais transmis la langue à ses enfants, qui ont grandi en parlant le français et l'anglais, sa fille Cécile Gallon (ma grand-mère) se souvenait affectueusement qu'il parlait en breton, et elle a toujours ressenti un lien avec la langue. Le souvenir de sa joie reste gravé dans ma mémoire jusqu'à aujourd'hui.”, Anna Luisa Daigneault, Program Director, Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. Lite Linguistics is a TikTok channel focused on world languages. They recently produced a video on Breton language. This is how they explained it. "Hello welcome to lite linguistics Meet Breton a Celtic language spoken in the Brittany region of Northwestern France Around 275 BCE there were Celtic languages all over Europe, spanning all the way from Iberia to Anatolia but as the Latin speaking Romans and the various Germanic tribes came in they pushed these Celtic peoples out. Which leaves us with just these modern day darker green Celtic languages. Now Breton is the only Celtic language remaining on the European mainland but even then it was brought over by Celtic speakers from Great Britain around the year 800 AD. So it's more closely related to Welsh and Cornish than it is to any extinct Celtic continental language the government of France has tried to put it down many many times throughout the centuries. Breton has no status at the national level. Breton is the only Celtic language that has no recognition in their national government but despite all the opposition people keep speaking it and keep learning it." Louis Kuter, editor of Bro NevezBREIZH AMERIKA PROFILES | Lois Kuter