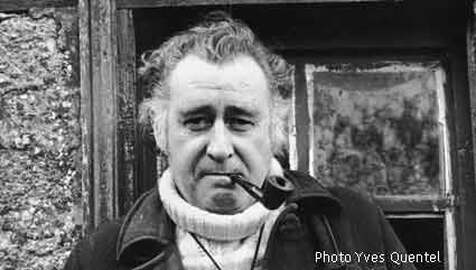

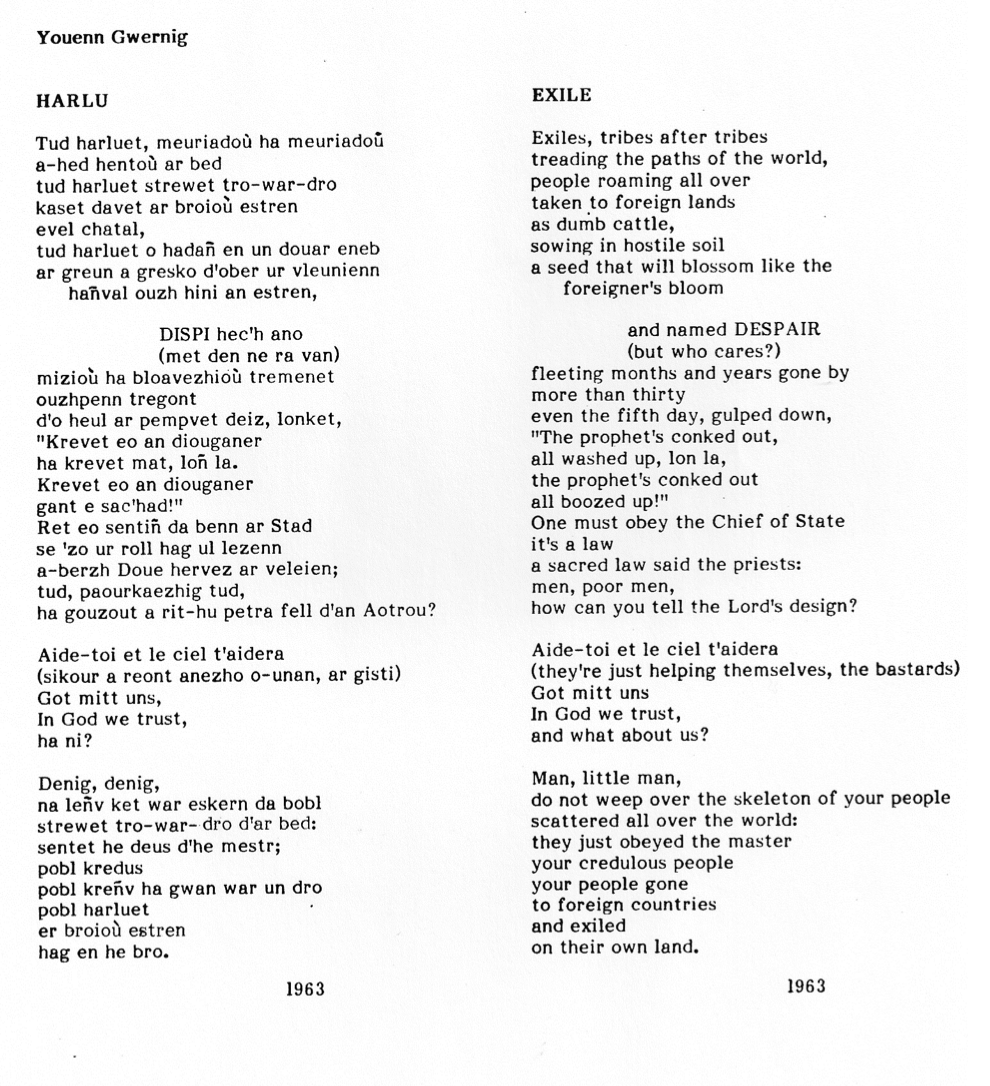

AN INTRODUCTION TO YOUENN GWERNIG Written by Lois Kuter - August 1983, ICDBL newsletter Youenn Gwernig came to the United States in 1957 at the age of 32. His reasons were not different from those of other Bretons who had preceded him or who followed later. With a sister already in New York, emigration seemed the best means to solve the difficult problem of earning a living. But there was also the problem of "feeling at home" at home -- an uneasiness which was perhaps more subconscious than conscious. Although today Brittany seems alive with a youth determined to revive their heritage and create a new one of their own, in the early 1950's Bretons concerned about the future of their nation might well have felt disheartened. Some felt it would be better to feel like a stranger elsewhere. Arriving in New York, Youenn Gwernig worked as a dishwasher and waiter, but most of his 12 years there were spent using his woodworking skills in a factory which reproduced Louis XV style furniture--a job of dull assembly line work and three hours of subway commuting each day. With the supplemental income of his wife Suzig who worked in the cont check of a bowling club, the Gwernigs were able to provide for three daughters- Annaïg, Mari-Loeiza and Gwenola--and indulge in some of the taken for granted comforts of American life. But the money ran out when Suzig's mother (also in the U.S.) needed hospitalization and an operation. Without insurance, the bills piled up. In 1965 mother, daughter and granddaughters returned to Brittany while Youenn stayed behind to pay off the debts. By the time he got back to Brittany in 1969, the debts were paid and he was as poor as when he had left Brittany, but Youenn Gwernig had also become known and respected in Brittany as a Breton language poet. If the United States holds memories of long and hard work hours, it also holds memories as the place where he really started to write--and his writing was in Breton. During the years in New York Youenn Gwernig combed the Breton collection of the New York public library and sent for books from Brittany. The return mail carried his poems and stories to Al Liamm.* Residence on Ryer Avenue in the Bronx introduced Youenn Gwernig to the unmelted pot of urban American cultures. We meet the people of his American experience in his songs, poems and stories, But, one of Gwernig's best known acquaintances in the U.S. was another Breton, Jack Kerouac, whose family (Le Bris de Kerouac) traces back to the Côtes-du-Nord before its arrival in the "New World" in the 18th century. Born in Lowell, Massachusetts, Kerouac was proud of both his Breton and Native American roots.** Youenn Gwernig is not known in Brittany today, however, because he befriended a famous writer. He is known ‘in his own right as a singer, poet, and wood sculpter, as well as defender of Breton freedom to be Breton, It was the desire to be Breton in Brittany as well as the desire to rejoin his family that took him back in 1969 to stay. A sense of freedom was immediate. In an article written in 1980 about Gwernig, Yvon Le Vaillant recounts how, at 6 a.m. on his first morning back in the town of Huelgoat in the Arrez Mountains of central west Brittany, Youenn ran down to the lake bordering the town and yelled "No subway today!" Reassured by the echo of the lake he went back to bed.*** Since his return to Brittany, Youenn Gwernig has lived in a small village just outside Huelgoat--a singer, poet and sculpter who loves long walks in the wild countryside and forests of the area. He continues to sing and to write and to insist on the freedom to be Breton in Brittany. The freedom to be a Celt is an important theme in all of Gwemig's writing. It was in the anonymity of American crowds and the greyness of New York City that he came to write down many of his thoughts about his own identity, his feelings for his native country, and the experience of emigration. We have two contributions to this special newsletter which present Youenn Gwernig to you. First, the poem “Harlu" ("Exile") which speaks for itself. This poem has appeared in the Breton language journal Al Liamm as well as in Yann-Ber Piriou's bilingual Breton/French collection of poetry, Défense de cracher par terre et de parler breton.**** Upon request, Youenn Gwernig has supplied us with an English translation for this news- letter. The second presentation of Youenn Gwernig is by means of a review of his novel La Grande tribu by another Breton emigrant, Hervé Thomas. Much of La Grande Tribu was originally published in Breton in Al Liamm as a series of short stories. The review will tell you that Youenn Gwemnig writes for many other emigrants who have crossed the sea to America. Notes * Al Liamm comes out every two months and is available by sub- iption c/o: Yann-Ber d'Haese, Pont Keryau, 29290 Pleyben Brittany (France). See the U.S. ICDBL Newsletter No. 2 for a description of this important Breton language publication. La Kerouac writes of his search for his Breton roots in his book Satori in Paris (NY: Grove Press, 1966). ** - Yvon Le Vaillant "Le Barde des Monts d'Arrée," Le Nouvel Observateur 825 (30 Aug.-5 Sept 1980), pp. 34-35. For an autobiographical sketch of Youenn Gwernig see: "Barde et Breton d'instinct" in Autrement (special issue: Bretagnes les chevaux d'espoir) 19, June 1979, pp. 74-77; "Pennad Kaoz gant Youenn Gwernig" (interview) in Evid ar Brezhoneg 178, June 1980, pp. 1-6; and "Youenn Gwernig--B.À.S. No. 271" in Ar Soner (special 4Oth anniversary issue) 273, 1983, pp. 18-19. **** Yann-Ber Piriou. Défense de ( er par terre et de p: Breton - poèmes de combat, 19 ° (Paris: P. d. 1971). This collection of poe by 20 contemporary Ereton language poets is highly recommended to readers. Youenn Gwernig poem - HARLU (Exile)LA GRANDE TRIBU. Youenn Gwernig (Paris: Grasset, 1980) Review by Hervé Thomas, 1983 Among all the reasons compelling a Breton to emigrate, there is one that stands out. Some of us who have emigrated are conscious of it, and for more of us it's all the way in the back of our minds. At one point we realize that the elements important to the realization of a harmonious and mentally and physically satisfying existence are not there. We have been denied the right to think that those elements are there. Youenn Gwernig describes this in La Grande Tribu through the main character, Ange Rosso, a Breton emigrant to New York whose name come from his Italian father who worked as a stone cutter in the quarries of western Brittany. Ange Rosso cannot forget the reasons that. made him leave his nation. Not unlike Youenn Gwernig himself, he was a native Breton speaker, an accomplished piper, and a person directing his life according to the natural tendencies that make Celts behave, adapting their own cultural, emotional and physical capabilities to their natural surroundings. Ange Rosso has undoubtedly a Celtic atavism. “The worst was the sudden transformation of mentalities... like, all of a sudden everybody was ashamed of what they used to be... I do not believe that I am one to put the bottom on the ball. I had even dreamed of a Breton Nation which would have found again its memory, its culture, îts pride, in order to finally get hold of its history and open itself to the future. But not the future that was starting to develop under my very own eyes, and was com- ing to look more and more like a voluntary genocide. I was starting to look at myself as a remnant of a forgotten era, like a displaced person, and with all evidence as one who was rejected from his sphere. My wife, craving for modernism, left me because of my lack of social ambitions and my Celtic esoterism, predicting for me the dim future of ending up as an absolute derelict outcast. All of a sudden my entire nation seemed to feel like my wife. How soon was my nation going to leave me?" (pp. 182-183). Ange Rosso felt then that he was lost in his own natural environment. Therefore, he took steps to evade the sights of destruction that his sensitivity exposed him to, and came to the United States. When one reads Gwernig's book, one is appalled by the traumatic experiences Ange had to face before he decided to make the move (the departure of his wife, the exodus of Bretons armed him in search of jobs, and the loss of his best friend--almost a son to him--in the Algerian War). My purpose here, however, îs not to describe those experiences in detail, but to help the reader be more aware of some of the thoughts and feelings that are part of the experience of Breton emigration. For those of us who have emigrated, the fact that we did not have to deal with such tragic events does not mean that we were not aware of the inadequacies inherent to the transformed nation in which we were living. Some of us close to our roots tried to react against modernistic bureaucratic oppression by using clumsy methods, violent reactions, and reckless behavior. Some of us tried to find a happy medium between the modern presentations and the concrete elements inherent to our culture, habits and emotions. But, deep down in our soul, we knew that the principal elements which would contribute to our quest for recognition, respect and acceptance by foreign powers and nations (France and nations within France) were smothered by the invasion of artificial ideas born out of modernistic greed and ancient drive for the assertion of power over others. The very young people in Brittany--those able to understand words--have been listening to the older generations, and those generations never fail to bring up stories about generations before, for it. is imbedded in their soul. But, by the time the young people get to school they have already been exposed to a different world which offers them few options--options which are only the sum of added confusions. Although disenchanted by the thinking of some members of the Breton Nation, Youenn Gwernig is clear about the options he feels each Breton must face. "It is the duty of our people to know whether they belong to, and in, Brittany or not. If they are stupid enough to let themselves be drawn into deep French waters or other waters, it is not fair to ask the rest of the world nations to try to correct the result of their own listnessness . . . (Page 264, in answer to a situation where terrorism was presented to Ange Rosso as a means of exposing Brittany to the rest of the world), For those of us who have become conscious of our heritage before or after leaving our nation, it is very easy to think and act as a member of the Breton Nation. We cannot speculate about the outcome of the thinking of the next generation and the generation after that. However, we do feel that Brittany will never cease to exist as a Celtic nation with its own identity. By now readers may have given up hope for a succinct review of La Grande Tribu. Nevertheless, the above comments are necessary to expose readers to the true reasons of Breton denial of their own identity when at home and when travelling to find smaller communities of their own in which they can act as Bretons, speaking Breton, and in which they will gain a sort of experience that will be appreciated the day they are back where they belong. Emigration is not an easy choice for any of us; but as soon as we choose to leave, we end up being with individuals from our own nation seeking the warmth that was lacking in our own surroundings at the time we left. We do find it instantly as soon as we meet other Bretons in places where we can relate to each other. As people belonging in the same place--Brittany--all of a sudden we are aware of our own identity. Those who never spoke Breton try to find every excuse to come up with a few words, even though when they were within the French State boundaries their Breton accent marked them as idiotic "Ploucs" and, out of shame and insecurity, they denied their own identity. Youenn Gwernig's book is a pure rendition of Breton (Celtic) attitudes toward life, its realities, determined thoughts, and a certain way of looking around and living one's life rather than letting it simply go by unnoticed. His presentation of Ange Rosso's experiences (and through them, some of his own) are expressed in a typically Celtic manner, with Breton wit, irony, optimism vs. pessimism, and a fatalistic sense of humor which stresses the importance of living and expressing oneself within the boundaries of actual realities. Youenn Gwernig's sense of humor tends to be very subtle, but very understandable for those who are prepared for it; for others it may be taken as a bitter satire of the world in which we are living. Youenn Gwernig is never confused about issues, values, and forces. His attitude cannot be simplistic. He expresses this thoughts with a true understanding of the difficulties of communicating with concerned but ignorant individuals. It is poetic, realistic, humorous, sad, and a pure definition of a Celtic way of dealing with adversity. The whole story is written with an ironic undertone. Gwernig has rendered in a foreign language (French) the particular style in which a Breton speaker expresses himself. He has described with rare accuracy the life of every Breton in New York, for the form is the same for each one of us--only the details are different. His book is more than a novel. It is a reflection in an excellent literary style of the life, soul and hopes of a real Breton. Bibliography and Discography of works by Youenn GwernigPoetry collections: An Toull en nor (le trou dans la porte). Locmaria-Berrient: Âr MajemEdition, 112 pages, 1972. An diri dir/Stairs of Steel/Escaliers d'acier. Locmaria- Berrien: Ar Majenn Edition, 1976 (trilingual). Novel: La Grande tribu. Paris: Grasset, 1980. (To be translated Into English? - rumors of possibility) Youenn Gwernig regularly contributes to various Breton language publications, most regularly A1 Liamm. Records: Ni hon unan. Arfolk MK2. 45 rpm. Distro ar Gelted (return of the Celts). Arfolk SB309, 1974 E kreiz an noz. Velia 223 0045. 1977 Youenn Gwernig. Production People, 1980.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

June 2024

Breizh Amerikais an organization established to create, facilitate, promote, and sponsor wide-ranging innovative and collaborative cultural and economic projects that strengthen and foster relations and cooperation between the United States of America and the region of Brittany, France. |

Copyright 2014 - All rights reserved - Breizh Amerika - Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed