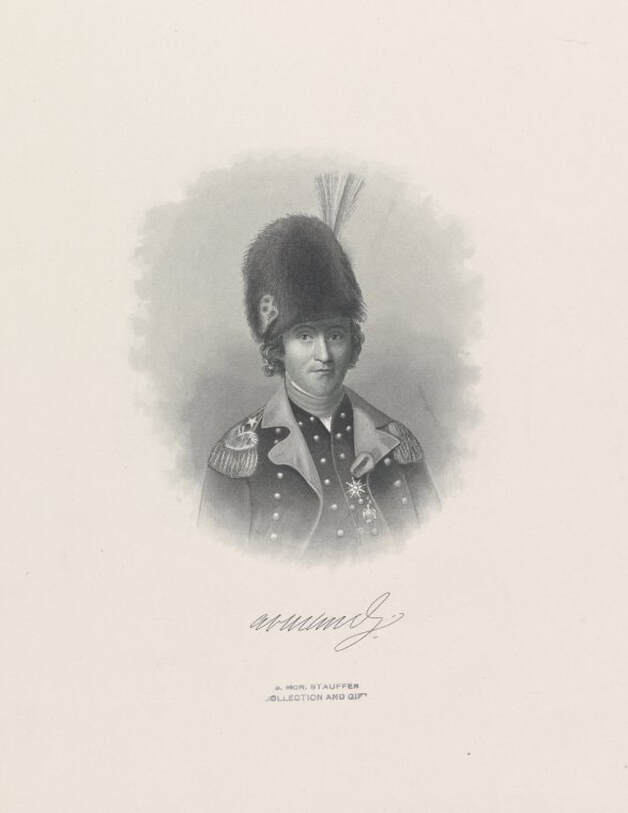

The Marquis de La Rouërie: A Breton Hero of the American Revolution Charles Armand Tuffin, marquis de La Rouërie, is a hero of the American Revolution whose contributions to the cause of American independence have been largely forgotten by history. A nobleman and military officer, de La Rouërie was a friend of George Washington and fought alongside the Continental Army as the leader of the Free French Corps, also known as "Colonel Armand". Despite his bravery and dedication to the American cause, de La Rouërie has been largely overlooked by history, and his name is not as well-known as those of other figures of the American Revolution. However, his contributions to the war effort and his friendship with Washington make him a significant and fascinating figure in the history of the American Revolution, and it is time for him to be recognized as the hero he was. In this article, "Colonel Armand, of the Revolutionary War" by J.G. Rosengarten, the life and contributions of Charles Armand Tuffin de La Rouërie are explored in depth. Rosengarten's article from 1898 delves into de La Rouërie's background and motivations for supporting the American cause, as well as his life after the American Revolution. This article provides valuable insights into the life of a lesser-known but important hero of the American Revolution. Source: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography , 1898, Vol. 22, No. 2 (1898), pp. 234-242 The Marquis de La Rouërie: A French Nobleman's Service to the American CauseOne of the brilliant Frenchmen who figured with distinction in our War of Independence was Armand, Marquis de la Rouerie. He raised and commanded a legion which distinguished itself in our service. In the Revue des Deux Mondes of April 15,1898, is the first part of a sketch of his life, drawn from original and little known printed sources by T. G. Lenotre, and the story, continued in successive numbers for May and June, well deserves to be told in an abridged form, as throwing light on one, at least, of our brave allies. Armand de la Rouerie was the complete personification of a gentleman of the ancien regime of the old school of France. He had alike their faults and their virtues, easy morals, carelessness, bravery, pride, imprudence, chivalric heroism, and an absolute contempt of death. In the French Revolution he showed courage, pride, stoicism, astonishing in a man whose youthful frivolous existence seemed a preparation only for pleasure and idleness, under the training of a dissolute uncle, a Breton gentleman, who, after thirty years with his regiment or in his quiet country home, inherited a fortune and spent it in extravagant living in the fashion of the time. He was the guardian and mentor of his nephew, Charles Armand Tuffin de la Rouerie, flag ensign in the regiment of French Guards. This lad, at seventeen, was brought to Paris and taught the pleasures of life there. With a generous and impressionable heart, a bright face, and an attractive figure, he showed himself an apt pupil. Left by the early death of his father to the care of a young mother, pretty and fond of pleasure, he received a brilliant rather than a solid education, spoke English and German fluently, danced Well, and was ready to follow any impulse given him by his elders. He became the leader of the young men of his set, had love affairs and quarrels, in one of his duels severely wounded his own cousin, took opium, but, restored to life, fled to Geneva, resigned from the army, and then, resolved to regain by some bold step the reputation perilled by his mad career, bade good-by to his mother, and with three servants sailed for America, reaching that country in April, 1777. He left in France a natural son, to whom he gave his name, and who later in his life figured in his adventurous career. The enthusiasm of the French nobility for the cause of American independence was one of the striking incidents in French history. Abandoning their luxurious lives, they seemed to draw fresh and wholesome influence from the plain and sturdy people for whose liberty these soldiers of a king gave their whole strength. It was more of a passionate outbreak than a careful and well-considered adhesion to republican ideas. It soon influenced their countrymen, who took it for a serious conviction of the truths proclaimed by the American patriots. The Marquis de la Rouerie was one of the first to reach America; he got there before Lafayette had left France. He came in search of liberty and ad ventures, and he found both in abundance. After a passage of two months, his vessel was attacked by an English frigate, which destroyed his ship, but with his three servants he swam ashore, naked, all his supplies of every kind being lost in the wreck. He obtained from Washing ton permission to raise a legion, but sought in vain for vol unteers. The French were not popular ; the first comers had offended the Americans by their pretensions and their bad behavior. The cool reception given to Armand might well have sent him home, but he persisted, bought for two thousand four hundred livres a free corps formed by a Swiss major, and was ready to take part in the campaign of 1777. Commanding an irregular body of troops, with absolute liberty to go where he liked, the war of surprises and ruses, nights passed in the open air, the attraction of danger, improvised camps, the life of a partisan, without thought of the morrow or care for the day, without law, without prejudices, without subjection to authority, all this suited him so well that he soon gained the reputation of a hero and quite unfitted himself for the narrow course of European life. Colonel Armand, as he called himself, became as popular as Lafayette, and Chastellux, meeting him at dinner at the French minister's (Luzerne) in 1780, spoke of him as cele brated in France for his adventures with an actress, and in America for his courage and capacity. He pleased the Americans by the simplicity with which he adopted republican morals, he won the affection of the French by his bravery and modesty, he gained the admiration of both by his heroic courage and his unconquerable firmness. The legion which he commanded was destroyed at the battle of Camden in South Carolina. He went to France, bought all that was necessary to arm and equip new partisans, offered them to Congress, reorganized his legion, at Yorktown led an attack on the enemy's works, and Washington rewarded him by giving him the choice of fifty volunteers to reinforce his legion. Everywhere he was at the fore-front, showing himself indifferent to every danger, seeking the most perilous post, and, the war over, remained in America to urge due rewards to his countrymen. The first to come, he was the last to leave, and returning at last to France, found all positions filled, and, tired of solicitation, retired to his estates to complain of ill-treatment from his own country. He brought home from America nothing but the Order of the Cincinnati and fifty thousand francs of debt, an old companion in arms, Major Schaffner, and opinions of the most advanced kind. His only rank was that of brigadier general of the United States. In 1785 he married a rich woman of rank, who died in 1786. De La Rouërie returns to France, leader of l'Association bretonne Tired of his life as a country gentleman, he threw himself into the struggles that preceded and presaged the coming storm of the French Revolution. He was one of a delegation of Breton noblemen sent to Paris in 1788 to offer their services to the King, landed in the Bastille, left it in a blaze of glory, was both revolutionist and royalist, full of activity in pressing his claims, tore down his ancestral home to replace it by a vast castle, still standing unfinished, surrounded it with trees from America, still growing, but finished nothing, and spent most of his time and fortune in Paris on another actress. He threw himself into politics, but could not secure the support of his fellow-noblemen, quarrelled with his brother, and had a curious love affair with his cousin, a young woman who shared his aspirations and the tangled web of royalist conspiracies in which he engaged with characteristic zeal, passion, and want of judgment. He rivalled Lafayette and Lauzun and La Roche jaqueluein in public notoriety by his wild career, and won the praise of Chateaubriand and the admiration of the law students of Rennes. His first ally was his old American companion in arms, Major Schaffner, a poorly educated man, who never learned to speak French intelligibly; his only support at first was a half crazy Breton nobleman, whose chateau was the gathering place of all the discontented royalists. Armand de la Rouerie was at last recognized by Comte d'Artois, brother of the King, then in prison, and visited him at Coblentz, taking along his fair cousin, his valet, his barber, and his body-servant, and set on foot a series of conspiracies against the French government which gave it a great deal of trouble, caused the loss of many valuable lives, and did little real service to the cause of the King. He enlisted one of his old comrades in America, Georges de Fontevreux, nephew of the Dowager Princess of Deux Ponts, who had served with distinction in both France and America, spoke English and German fluently, and was ready for any madcap adventure. Armand, on his return from the exiled court, stayed in Paris long enough to renew his old acquaintances, and with characteristic thoughtlessness revealed his secrets to those among them who were as devoted to the republic as he was to the crown. Returning to his country home, he became the head of a conspiracy which is still famous in French history. He brought together all who were dissatisfied with the republic, honest loyalists like himself, men who were outraged by the removal of the faithful old priests so dear to Breton piety, making each parish the centre of a group sworn to avenge the injury done their pride as royalists or their piety as good and fervent Catholics. He organized local councils and bodies representing them. He gathered around him men of all ages and all types, and asked of them no act of devotion which they were not ready to do at the sacrifice of life, if need be. As chief he showed an utter want of capacity, and this fault was heightened by want of means to arm his forces and to give them the opportunity of living and of executing his wild and fantastic orders. He lived in his castle on a grand scale, with fourteen servants, ten saddle-horses, and an endless succession of peasants, spies, recruits, emissaries (table free to all), and volunteers mounting guard and patrolling his estate. He got money from the exiled court through agents who carelessly revealed his secrets to friends in Paris who were spies for the government, thus putting at risk his life and that of every man sharing in his conspiracy. Supported by the exiled princes, Armand de la Rouerie was confident of success. He commanded in their name in Brittany, and instead of the legion of adventurers and deserters he had led in America, was at the head of a considerable army of peasants, and his staff was made up of distinguished noblemen. His chateau was the general head-quarters, his chief of staff his fair, if frail, cousin Therese de Moelien, who rode about the country dressed like an Amazon, with gold epaulettes and the Order of the Cincinnati attached to a blue ribbon, and a white plume in her hat. The chateau was regularly garrisoned, a score of troopers exercised daily on the lawn, sentinels kept guard, the entrances were barricaded, and nightly gatherings filled the house with light and noisy enthusiasm. Besides drawing freely on the royal purse, his well-to-do allies gave him a year's revenue. Six thousand muskets were secured, four guns were mounted, abundant supplies of ammunition were brought from England, and cartridges were made in a secluded house which served as an arsenal. Ready by the spring of 1792, General Armand obtained from the royal princes, brothers of the imprisoned King of France, a formal order giving him full power. The royalist army under the Duke of Brunswick was to march from the north, Armand with ten thousand men from the west, and, concentrating at Paris, the King was to be freed, the Assembly dispersed, and the royalists again put in power? On a given Sunday peasants and noblemen crowded the chateau ; the former were supplied with food and beer, the latter with champagne, and gaming tables were started for their amusement. At last the Marquis Armand de la Rouerie appeared in full uniform, his commission was read, and he addressed the crowd in energetic phrases. This was the first scene in that royalist enterprise in which for long years life and fortune were wasted by men who underwent every sort of hardship, nights without sleep, winters without shelter, proscribed, in hiding, shot down like wild beasts, and twenty years after even Napoleon spoke with respect of the little band that still fought on ; the peasants led by their priests, the noblemen abandoning their homes, a price set on the head of their leader, who was sheltered in one chateau after another by noblemen always ready to protect the representative of the crown and of the church. Among the peasants were men of real genius for the sort of war thus set on foot, and both the wild nature of the country and of its inhabitants enabled them to resist invading armies of the republic far larger in number and far better equipped. Armand was the head of this force, appointing its chiefs, supplying arms and food and money, planning its operations, and responsible alike for its successes and its failures. All this time he was in close contact with men who betrayed his every movement, almost his very thoughts, to the republican leaders in Paris. One of these spies lived in daily intercourse with Armand and his friends, and went from their intimate meetings to Paris to report everything that was said and done. He even persuaded the royalists that the republican leaders were their friends. Armand sent this chief conspirator to represent him in London, and took him along in his conferences with the leading royalists. From these meetings this clever spy hurried to Paris to make his reports, returning with other confederates to keep alive the intrigues in which Armand and his friends were going deeper and deeper. For three months this able scoundrel lived in daily contact with the royalists in Jersey, Dover, London, and Liege, was presented to the Comte d'Artois and his ministers, pretended to help their plans, and kept up correspondence alike with the royalists, the Breton conspirators, and the republican government. Armand was stirring his peasant soldiers and his noble officers to all sorts of desperate enterprises, often leading them to acts of heroism in open combat, earning the confidence of his fellow-royalists and inspiring them with his own unshaken faith in the triumph of the good cause, when he should enter Paris at the head of an army of peasants, singing their old Breton songs and full of hope for King and Church. De La Rouërie's last daysAmong the warm supporters of Armand was one of the Breton noblemen, who remained in his old chateau in this eventful month of January, 1793, with wife and daughters and a retinue of servants. There Armand had found shelter repeatedly, and there he came on January 12, 1793, after weeks spent in tireless activity, visiting the chiefs of his local bands, changing his place of refuge every night, sleeping sometimes in the forests, sometimes in hidden huts or caves. His indomitable tenacity of purpose, his success in escaping pursuit, and the romantic circumstances of his tragic death left traditions that are still familiar legends in this part of Brittany. His last visit ended in his death on January 30, 1793, after a desperate illness, in which his faithful friends sought to give him every care; but his horror on suddenly receiving news of the death of the King on January 21 ended in his own. The grief of his faithful friends was heightened by their anxiety, and a last resting-place was secretly given him in the grounds of the chateau, while measures were taken to preserve its identity. The certificate of death, hidden at the foot of an oak, was found there in 1835, still legible. His private papers were taken for greater security to the chateau of another of his faithful allies, and for a few days all passed tranquilly in the house where Armand ended at forty-two his adventurous life. Following closely came the visit of Chevetel, who pretended to be one of the royalist conspirators, while he was actually a spy in the service of the French republic. During Armand's last illness, Chevetel sent a report to him of the visit he had made to the royalists in Belgium, and another to the authorities in Paris with the details learned during his stay with the conspirators. Returning to Brittany with a fellow-spy, armed with authority to use soldiers and police, with powers of life and death, so little confidence had the government in these agents that other secret agents were sent to follow them and report their every action to the central authority in Paris. Even the two spies mistrusted each other, and each tried to have the other arrested and imprisoned. Chevetel maintained the character of being a royalist only to penetrate the secrets of Armand's friends and to reveal them to the government, while he tried hard and successfully to keep up his disguise. Finally both appeared at the chateau where Armand had died, and there arrested the whole family of his friends and sent them to Paris, where they met death on the scaffold with heroism worthy of a better cause. These spies even unearthed the remains of Armand and made a detailed report of its condition, still preserved in the archives of the government in Paris. The head of Armand was put on a pike and exhibited to the gaping crowd. The chateau was pillaged, yet it still remains a mute witness of the dreadful scenes of those trying times. Even the room in which Armand died is kept as it was at the time of his death, and his tomb in the woods near the house is a pile of rough stones, surmounted by an iron cross, of which the arms bear the insignia of Brittany and the lilies of France, and the inscription preserves the legend, " Armand, Marquis de la Rouerie, died January 30, 1793 : he died of his fidelity to his King." A descendant of his last and faithful friend still lives in the old chateau, an old woman who for more than eighty years has occupied it, preserving the memory of its hero, whose portrait still hangs on its walls. For him, her memory is full of tender indulgence and admiration, and her fidelity is worthy of her glorious race, of men faithful to their King at every sacrifice and ready to give life and fortune in his behalf. The story of the hardships inflicted on the family that sheltered Armand in life and death is characteristic of the mingled horrors and levity of that awful time. Dragged from one town to another, threatened with death, insulted, robbed, receiving protection from the agents of the government only in the hope of plunder, their fate is part of the history of the period. The agents and spies quarrelled over the division of their spoils, and the government, after using them to bring the poor victims of their loyalty to the scaffold, sent one to Venice to watch their own agent; the other lived to a venerable age, having served in succession every dynasty of France down to his death. The memory of poor Armand passed into oblivion, and only now is restored to the light of day by the faithful chronicler of his sad story. M. Lenotre has traced, out of forgotten archives, every step of Armand's last days and the fate of his fellow-royalists, conspirators for the cause of the King. Is there any trace of the " Major Schaffner," the American who shared Armand's adventures in both the Old World and the New, or is he, too, a shadow? What Armand and his fellow Frenchmen did for this country in its time of need may well justify our interest in their subsequent career. The story of our French allies can be finally told only by tracing out their lives after their return home. This it is that M. Lenotre has done for Colonel Armand. "Colonel Armand, of the Revolutionary War" is an article from The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 22.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Blog Archives

June 2024

Breizh Amerikais an organization established to create, facilitate, promote, and sponsor wide-ranging innovative and collaborative cultural and economic projects that strengthen and foster relations and cooperation between the United States of America and the region of Brittany, France. |

Copyright 2014 - All rights reserved - Breizh Amerika - Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed